We all know the challenges of the last three years. We’ve read the headlines and heard the research about the impact of COVID-19 on education. Given the stress that the pandemic put on educators, reading about the continued low rates of growth and the increasing inequity among students can be quite overwhelming. Teachers and administrators are well aware of the issues; they see them play out in their classrooms every day, where it is estimated that more than half of students enter below grade level. The question of how to best address these issues has led to a debate over teaching grade-level content versus differentiating based on each student’s level. To help teachers navigate this question, our High Growth for All project has identified 10 effective strategies—the Transformative Ten—to help teachers differentiate while still providing access to on-grade content. The first strategy centers on providing supplemental instruction time so that kids can practice skills they’re still developing.

About High Growth for All

High Growth for All started with NWEA researcher Andrew Hegedus and his review of longitudinal achievement and growth data. Using data from 700,000 students in 24,500 public schools that test with MAP® Growth™, our interim assessment, he set out to identify high-growth schools. Enter Chase Nordengren, another NWEA researcher, who built upon this research by conducting in-depth observations of the classrooms of four highly effective teachers at two high-growth schools in Schiller Park, Illinois’s School District 81.

Over the course of the 2022–2023 school year, Chase recorded over 75 hours of instruction and 12 hours of interviews with these teachers. From this research, he developed the Transformative Ten, ten instructional strategies that can be applied to any grade or subject to both support differentiation and provide access to on-grade content. Here in Teach. Learn. Grow., we will examine each of the Transformative Ten in depth over the course of this school year, starting with Strategy 1: Provide supplemental learning time for targeted retrieval practice.

Supplemental instruction for all

Supplemental instruction is a common component of most classrooms. In a previous post, I referenced a WestEd survey that named the need to differentiate and personalize learning as one of the top three reasons teachers turn to supplemental resources.

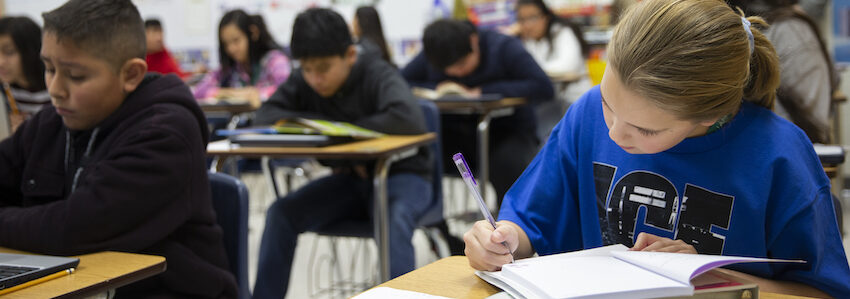

When we think about supplemental resources and differentiation, we tend to think about students at the extremes: those who may need support to access on-grade content and those who are whizzing through on-grade content at high speed. But targeted differentiation and supplemental instruction time are valuable for all students.

Schiller Park has implemented an approach to supplemental instruction that leverages multiple researched-backed strategies. Instead of implementing a pull-out model for below-grade support and above-grade enrichment, they have created a supplemental learning block in which all students are divided into small groups to receive targeted activities and instruction designed to support their understanding of current on-grade content. Let’s unpack the learning science behind Schiller Park’s approach to identify practices you can incorporate into your own classroom.

1. Practice good grouping

A key structural component of supplemental instruction for all is the formation of small groups. While long-term tracking by ability has been shown to have negative effects on both achievement and confidence, short-term, flexible groups designed for a specific purpose have been shown to support learning.

Targeted differentiation and supplemental instruction time are valuable for all students.

If your school tests with MAP Growth, your Class Profile Report is a good place to start when thinking about groupings, as it provides a high-level picture of the academic diversity of your class. Next, formative assessment that zeroes in on the skills and concepts related to your current whole-group lessons should form the foundation for your groupings. You’ll want to have recent, relevant evidence of students’ knowledge of the current topic. Thankfully there are a lot of quick ways to gather this evidence, including classroom conversations, student work, and short, frequent, ungraded assessments.

Once you have created your initial groups, formative assessment data can inform the learning goal for each group, and the learning approaches, activities, and type of grouping that support this goal. As you progress through the whole-class core content, use ongoing formative assessment to alter both your group composition and learning goals as appropriate. Because each group’s learning goals are targeted to the current core learning, these groups should not be fixed over the course of the year or even the current unit but should be adjusted in real time.

Check out NWEA’s guidance for student grouping for more information on forming effective, short-term learning groups.

2. Get in the zone

As you gather your formative data and begin grouping your students and establishing learning objectives, keep students’ zone of proximal development, or ZPD, in mind. As a reminder, the ZPD is the sweet spot between what a student can do independently and what they can’t do independently just yet. The skills and content that lie within a student’s ZPD are ones they can access with teacher guidance and scaffolding.

I bring up ZPD here because regardless of what group they are in, all students need access to rich, engaging content designed with the end goal—accessing on-grade content—in mind. So, while some students may need to review or practice precursor skills, this is the starting point, not the end goal.

Unfortunately, grouping students has sometimes led to those in what are deemed lower groups being consistently subjected to less challenging, more skills-based content that is never connected to on-grade expectations. This can have a cumulative effect where students get further and further behind.

When designing your groups, learning objectives, and pathways, always keep the whole-group, on-grade content at the center of your planning:

- For students who need support to access on-grade content, what is the roadmap of scaffolds you will provide, gradually taper back on, and ultimately remove as students grow their knowledge? How will you know when students are ready to drop a piece of scaffolding?

- For students who can frequently, but not consistently, access on-grade content independently, what new models, contexts, problem types, or modes of instruction can you provide to help them move to full independence?

- For students who can consistently access on-grade content independently, what can you do to deepen and challenge their knowledge of this content? Remember that challenging content doesn’t always mean jumping to the next topic or grade.

Like the Transformative Ten, there are many scaffolding strategies that can be applied to multiple subjects and topics. Need more support on scaffolding? Check out our post on strategies for using scaffolding while still challenging students or this short module from the IRIS Center, which gives examples of different types of scaffolding.

3. Give kids some space

In “Maximum impact: 3 ways to make the most of supplemental content,” I highlighted some best practices for supplemental instruction. One of these practices is connecting supplemental learning to core content. I talked about the benefits of developing a web of connected concepts and skills, versus amassing a collection of isolated and unrelated facts. There is another research-backed benefit to connecting supplemental and core learning: doing so leverages the highly effective learning strategy of spaced retrieval practice.

To understand spaced retrieval practice, think back to your own experience as a student. If you are like me, your typical learning experience looked something like the following: Sit through a lesson on a topic. Practice that topic with a batch of similar exercises. Sit through a lesson on a new topic. Practice that with a batch of similar exercises. Rinse and repeat with a quiz every couple of lessons and a test at the end of the unit. (And how did you study for that test? Did you cram by reviewing all the information the night before? If you did, you are not alone.)

The problem is, research shows that although procedures like cramming may get you through your test, you likely won’t retain much of the information. To embed concepts into long-term memory, students need to practice retrieving it multiple times, ideally over a period of days or weeks.

When you connect supplemental content to your core work, you provide students with the opportunity to retrieve and apply what they have learned during whole-class work. There are a variety of ways in which students can practice retrieving knowledge during supplemental work:

- Before starting a small group lesson or whole-group supplemental instruction, have students do a “brain dump” of what they know about a current or recent topic. Students can do this individually and then compare their responses with one another. As students move through their supplemental learning, have them review their brain dump to look for connections and add new learning.

- After working on a supplemental activity, including independent work in an online program, have students pair up to share what they learned. Provide pairs with questions like those in “Putting it all together: Real examples of how to integrate supplemental content into your core work,” which prompt students to connect current work with past learning to build that interconnected web of ideas while simultaneously giving them practice retrieving previously learned content. Research suggests that retrieving information soon after engaging with it is more effective than repeated rereading, so build this or a similar activity into the last few minutes of your intervention block.

- As students progress through content, give short, ungraded quizzes. They are a fantastic way of helping kids practice recall. To make this even more effective, be sure to provide feedback that includes concepts students either forgot or didn’t remember correctly, as studies indicate quick feedback may increase learning. To get students used to this idea, compare quizzing with feedback to doing drills and being coached in sports. Although these quizzes can inform updates to groupings, goals, and assignments, don’t make changes too quickly. Students should be able to accurately retrieve information multiple times over a period of several days or weeks to demonstrate more than a short-term retention.

- Take advantage of mixed practice options offered by many online supplemental programs, like MAP® Accelerator™. This combines both retrieval practice and something called interleaving. Interleaving is where the types of questions or problems are mixed up. So instead of practicing 20 addition word problems, interleaved practice could be composed of word problems that require different operations, formulas, or procedures to solve. This type of practice forces students to actively select the appropriate strategy based on the context. When selecting products, make sure they provide immediate, high-quality feedback to maximize effectiveness.

4. Leverage technology wisely

The wealth of educational technology available today represents a large toolbox teachers can choose from for differentiation and targeted supplemental instruction. Among other things, technology can support formative assessment, boost engagement, provide opportunities for targeted and mixed practice, give in-the-moment feedback, adapt to students in real time, offer new ways for students to demonstrate their understanding, and connect learning to the real world. Our Instructional Connections program connects MAP Growth data to over 40 popular supplemental instructional resources. These predetermined learning pathways can be an effective and time-saving way to differentiate while retaining the flexibility to adapt supplemental instruction based on ongoing formative assessment.

Grounding in the learning objective is critical to selecting the right tool or product for each student or group of students. Learning goals should drive the product choice, not the other way around. While educational technology offers great options for teachers and students, as pointed out in our Transformative Ten white paper, “Teachers must still ensure that students receive the right content given their learning needs, that the content is engaging, and that students stay on task.”

When integrating technology into supplemental learning, you should still ask the same questions as when choosing nontechnology resources:

- Does my formative data indicate that this is the right content and level for this student?

- Will this product, pathway, or activity provide the right level of scaffolding and challenge?

- How will this product, pathway, or activity support access to, provide varied practice for, or deepen understanding of on-grade content?

One strategy at a time

Being a teacher has always been challenging, and the pandemic truly put every educator’s mettle to the test. Despite all the challenges you face, we know you are a dedicated and resilient group who will do whatever you can to help your students grow and learn. We hope the Transformative Ten will go a long way in helping your students thrive and achieve.

Here are some additional links to help you learn more about our work and strategy 1.

- High Growth for All: This site provides an overview of the research behind the High Growth for All project and of each of the Transformative Ten strategies.

- “Jump-Start High Growth Instructional Strategies with MAP Growth”: This guide gives insight into how MAP Growth data can be used to inform and support the Transformative Ten instructional strategies.

- “The Transformative Ten: Instructional Strategies Learned from High-Growth Schools”: This white paper gives an in-depth look at the research behind the High Growth for All project. It also provides more information and specific examples of how the Transformative Ten strategies were implemented in SD81.

- “Transformative: An NWEA story of extraordinary growth”: This video gives an overview of the work Chase did with Schiller Park teachers, which led to the development of the Transformative Ten.

- “Provide supplemental learning time for targeted retrieval practice | Transformative Ten #1”: This short video shows how Schiller Park approaches supplemental learning time for all students.

- “So many to choose from! 3 tips for selecting high-quality, supplemental digital resources”: This first Learn. Grow. blog post in our supplemental approaches series gives tips for selecting high-quality resources based on your reason for using supplemental content. It also provides links to five resources that can help you evaluate supplemental offerings.

- “Maximum impact: 3 ways to make the most of supplemental content”: This second post in our supplemental approaches series discusses three strategies—connecting to core content, leveraging metacognition, and student pairings—to maximize supplemental instruction.

- “Putting it all together: Real examples of how to integrate supplemental content into your core work”: This final post in the supplemental approaches series gives concrete examples of best practices for incorporating supplemental content into math and reading classrooms.

- “7 ways to use ZPD and scaffolding to challenge and support students”: This post lists seven strategies that can be used to scaffold content in multiple subjects. It also provides specific examples of scaffolding in reading and math.

- Retrieval Practice: This comprehensive website includes background information, links to research, and strategies related to retrieval practice. It features two guides that provide overviews, describe the benefits to students, and give suggestions for how to implement retrieval practice and spaced retrieval practice in your classroom.