Whenever Bill Gates discusses anything, it sets internet hearts aflutter. After all, the Microsoft founder and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation standard-bearer has a lot of experience and influence, especially in K–12.

Gates’s recent interview in The 74 touched on the future of math learning, a topic America must feel never leaves the headlines. With COVID-19 continuing to undermine our learners’ math foundations (especially our youngest and those experiencing socioeconomic inequalities), how can we attain success—and cultivate love—in math?

I asked several of my colleagues—educators, professional learning leaders, math experts—to weigh in on some questions that arose from the interview.

Do you agree that Americans “hate math”? Be honest, we’re going for real opinions here: did you hate math when you were in school?

Fenesha Hubbard: Although I have a degree in mathematics and taught middle school math, it took nearly a quarter of a century before I identified as a “math person.” I’m certain you can name a least five people who consider themselves to be “not a math person.” My certainty lies in the fact that our society has made “illiteracy in math acceptable the way illiteracy in reading is unacceptable,” as the late Bob Moses, founder of The Algebra Project and coauthor of Radical Equations, said.

Ted Coe: Somewhere along the way in my mathematics education career I learned to expect some sort of negative response when I told someone what I did. That person in the seat next to me on the plane? It might be easier and more comfortable just to tell them I’m a spy or something. At least things would be less awkward. “Hate” may be too strong a word, but there certainly seem to be ample amounts of angst and frustration. It’s unfortunate, really.

Tammy Baumann: I disagree. There is evidence to support that Americans “hate” that they do not understandmath, but not so much that they dislike the subject itself. Further, it’s socially acceptable to say “I hate math,” which precludes the need to confront what this is really about: math instruction focused primarily on memorization, little sense-making, and contrived context. If you spend some time reteaching a self-proclaimed hater-of-math using techniques that reveal why things work, how they are interconnected, and applications that are relevant, the story will change.

Anita Brown: It wasn’t until my freshman year algebra class that I had any struggles with math. My teacher was completely procedural in her thinking. That approach worked for some students, but it definitely did not work for me! My geometry experience was even worse. I didn’t know how to advocate for myself at the time, but it was clear that their approach wasn’t working for me.

In the interview, Gates touches on how low math scores point to the equity disparities in our schools. What would you add regarding the relationship between math and equity?

Fenesha: Understanding your academic identity is essential to operationalizing equity. A teacher’s academic identity is akin to their pedagogical beliefs, which can influence how and what they teach, their beliefs about students, and what they deem appropriate and necessary in the math classroom.

Empowering beliefs about math teaching and learning lead to actions that have a positive impact on our students. I believe that decisions rooted in right thinking will lead to right actions. Teachers can learn how to put equity into action in my upcoming book, The Equity Expression: Six Entry Points for Nonnegotiable Academic Success, which is a joint partnership between Corwin and NWEA.

Tammy: Gates focuses on geographical inequities. For example, inner-city schools do not have the resources and the degree of parental support afforded to their suburban counterparts. However, Gates does not touch upon the instructional inequities.

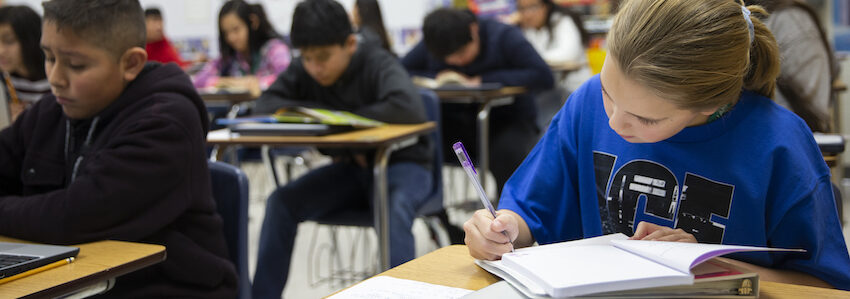

All students do not learn at the same pace and in the same manner. Typically, math is taught in a formal manner with the primary technique being direct instruction. This becomes more prevalent as students move from elementary to secondary schooling, with less focus on understanding and more emphasis placed on memorization. To meet the needs of all students, it’s necessary to expand instructional repertoire to include techniques that intentionally develop understanding and sense-making. It’s essential for teachers to have a deep understanding of mathematics themselves, and teachers who have this depth are more the exception than the rule.

There is a marked decline in the number of teachers with an interest in teaching math, and for current teachers, in deepening their own understanding of the subject. Therefore, many students do not receive the instruction they need, and thus instructional inequity surfaces.

Anita: If math is taught in a conceptual way that builds critical-thinking skills, then math and equity are absolutely inextricably connected. To offer students opportunities to think about authentic, real-world problems at every stage of their life is absolutely a social-justice issue. Our students are not “college and career ready” if they do not know how to manage time and finances, which leads to providing for themselves and their families. So absolutely I believe the relationship between math and equity is critical.

What are your recommendations for making math “more relevant and engaging,” as Gates says is necessary?

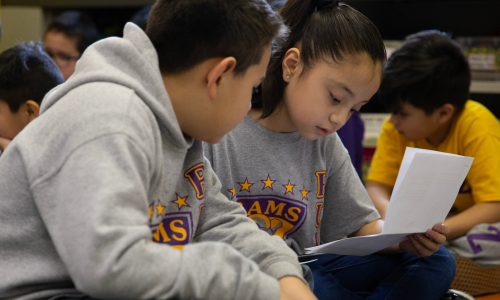

Kailey Rhodes: Slowing down and revisiting the foundations. If we believe all math is interconnected and spirals off itself, we must avoid assumptions that students are solid in their footing before we proceed. If students don’t truly believe the commutative property (3×4 is the same as 4×3), much of algebra will feel like voodoo! If students don’t understand place value, exponents will feel like magic! Often when adults are “retaught” math that they’ve either forgotten from disuse or never understood in the first place, not only will the concept gel, but they will also immediately see its tangents into other math. That’s true with our students, too.

Ted: Oh! There are so many possibilities! For example, we might start with evaluating our overall goals in the teaching and learning of mathematics. Are we striving to see who can collect the biggest collection of memorized things, like collecting puzzle pieces in a box? Or are we aiming for students to see how those pieces fit together and serve to craft a much bigger picture? Are we focused on (and rewarding) ways of doing things (procedural fluency, which is easily forgotten), or do we also emphasize (and reward) the importance of ways of thinking about things (critical thinking, which is with us forever)? Are we connecting to real life, when we can? For those parts that might not immediately connect to real-world examples, are we able to explain how they are important for a bigger picture? Everything in mathematics connects to something else. We must make those connections explicit for our students.

While Gates lauds the new ChatGPT, he doesn’t explicitly map out its math-education intersection. How do you imagine math class should change in response to the increasingly AI-laden landscape?

Ted: This leads me to think back to the excitement of IBM’s Watson years ago. It won Jeopardy. It could chew up massive amounts of medical data and spin it around in helpful ways. However, I never saw it applied in an educational sense where it would serve as a game-changer. Teaching, after all, is different from Jeopardy or providing medical recommendations. Classrooms have seemingly infinite variables in play. They are messy places that involve lots of people doing different things. I played around with ChatGPT a few months ago and saw some promise. It could do some wonderful things, but it simply didn’t do well with mathematics entrenched in language. This latest version, though, is remarkable. I believe it is a game changer. I can’t yet say how a math class might/should change, as I haven’t had the chance to dig deep and push it to its limits, but the Khanmigo work from the folks at Khan Academy is a noteworthy first attempt.

Anita: I don’t think math classrooms need to change in response to the AI-laden landscape. If anything, it further drives home the need for math educators to enable students to do bigger things with mathematics. Computers and calculators cannot do critical-thinking for students. The introduction of AI hopefully illuminates for curriculum writers, college professors, researchers, and other educators the urgency for us to respond with high-quality math teaching and learning that is worthy of our students’ time and attention. At this moment that means investing time in supporting teachers to raise the bar for all students. We do not have the luxury of “more time.” We must move with a sense of urgency to provide our students with a high-quality education at any cost.

Gates also mentions mental health and SEL post-pandemic as obstacles in education. Does this resonate with you or your work?

Anita: Mental health and SEL post-pandemic definitely changed the landscape for many. However, K–12 educators have seen that, especially in Title I schools, many students operate in the space of “I feel isolated. I feel alone. I don’t feel understood.” Their mathematics socialization has always been an “othered” experience. It is important that the Gates Foundation and others turn their attention to how we support full participation by all students, because now those historically marginalized students will, by proxy, benefit from the influx of resources and action in the face of our post-pandemic society.

Kailey: How can students care about anything—especially a subject that can feel sterile and disconnected, like math—when they don’t feel cared for? The ingredients of a successful math class are similar to the ingredients of any successful classroom. Do students feel liked? Valued? Honored as individuals? And the beauty of math is that it can get personal! We individuals have a lot of data about us: our birthdate, how many bottles are in our showers, the calories in our favorite cereal, how much we spent on our backpack. The more we individualize our students—using math class as yet another way to do that—the more our students are whole people. And what are we doing, if we aren’t teaching the whole child?

Complete the sentence: “When I got to the end of the article, I couldn’t believe they didn’t talk about______.”

Fenesha: When I got to the end of the article, I couldn’t believe they didn’t talk about teacher readiness to deliver high-quality math instruction. Academic identities, or teachers’ dispositions and beliefs that make up their relationship with math, are not fixed. Teachers and students have academic identities, whether they are aware of them or not, and our identities shape teaching and learning experiences. It is imperative that teachers continue to develop their math academic identities through professional learning and reflection. They can do this through the act of teaching, staying abreast on industry trends and best practices, and being self-reflective in their practice. It’s also important for educators to continue to be a math learner as well as a teacher. If we want to disrupt a system, we must be willing to disrupt ourselves.

Kailey: Teachers’ rights not to know and to relearn math. Teachers are learners, too, yet we often feel such pressure to know everything about math. I went to a cribbage tournament recently and was endlessly mocked for not being able to instantly compute the complicated points scoring. “Aren’t you a math teacher?” Even our math educators feel lonely as learners! How can we build a system of support, where teachers feel they can say, “I need some help understanding this concept, for myself as a learner, so I can teach it better”? How can we remind the rest of the world that the study of mathematics is not an ancient and complete field, but one still abuzz with discovery. We’re still mathing, folks! Let’s be gentle with each other.