In my last blog post, I talked about some of the strategies from Peter Liljedahl’s book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Grades K–12: 14 Teaching Practices for Enhancing Learning. In the book, Liljedahl outlines research-based strategies for moving students from merely mimicking rote steps modeled by the teacher to deeply collaborating with each other to expand their mathematical thinking.

In my last blog post, I talked about some of the strategies from Peter Liljedahl’s book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Grades K–12: 14 Teaching Practices for Enhancing Learning. In the book, Liljedahl outlines research-based strategies for moving students from merely mimicking rote steps modeled by the teacher to deeply collaborating with each other to expand their mathematical thinking.

I pitched the idea for that post in early 2025. So imagine my delight when I went to NWEA’s user conference, Fusion, in June and attended Beverly Broedlow and Rachel Stalford’s presentation about implementing these practices in their classrooms. Their enthusiasm for the approach and impact of their implementation was so incredible that I knew I had to find out more. I was grateful when they agreed to sit down with me for an interview.

Meet Beverly and Rachel

Beverly and Rachel teach at Great Valley Academy, a public charter school in central California for kids in transitional kindergarten through eighth grade. About 40% of Great Valley’s students qualify for free or reduced lunch, and approximately 10% are English language learners.

The school has a unique looping system, where teachers move with students for two years starting in first grade. The school also focuses on brain development and character, with an emphasis on building relationships and community. Beverly and Rachel teach the seventh and eighth grade loop, and between them they have a combined 26 years of experience.

Why shift to a thinking classroom?

My first question was what led them to try the thinking classrooms approach. Beverly and Rachel explained that they had been teaching together for about seven years when, after COVID-19 school closures, they both noticed more students displaying what they later recognized as mimicking behavior: students parroting back what their teachers had taught with little to no thought or engagement.

Assessments confirmed that kids were not building a deep understanding of math, and both were worried that their students were not adequately prepared for high school. They knew from MAP® Growth™ results that the students they were getting in seventh grade were also not coming in prepared—not just in math, but in all subjects. Beverly noted that some of their students were entering her class reading at a second-grade level, so the pair realized they had to do something different to reach them.

These observations caused them to reflect on their practice. Beverly realized, “Even before COVID, I feel like I was struggling with the fact that I was doing a lot of thinking and a lot of math, and the kids weren’t doing as much math. It was that idea of shifting the work and the thinking onto the kids, instead of the teacher.” It was Beverly who brought Liljedahl’s book to Rachel and told her she thought they needed to start implementing it immediately. Rachel began reading it, but they were both so excited by what it offered that they began implementing strategies before either of them finished the book.

Getting started

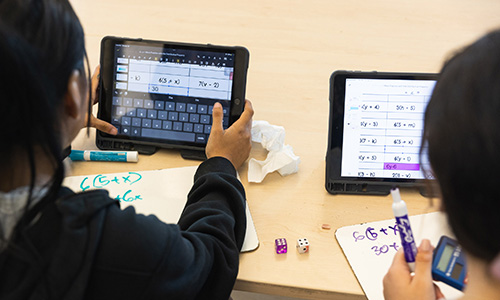

Following the book’s lead, Beverly and Rachel started by putting students into random groups of no more than three and having them work on vertical, non-permanent surfaces twice a week. They had already been using some of Jo Boaler’s mathematical mindsets tasks, so they put these to work as their thinking tasks. As a reminder, thinking tasks are designed to be so enticing that you can’t help but dig in and persist in solving them. The technique of frequent, transparent, and random grouping shifts the student dynamics and elicits more active thinking from students. And the vertical, non-permanent surfaces, which Beverly and Rachel’s students refer to as boards, support mathematical exploration, iteration, and within and cross-group engagement and discussion.

As the year went on, Beverly and Rachel incorporated more techniques from Liljedahl’s book but didn’t try to implement all 14 that first year. Interestingly, they also noted that they didn’t feel pressured to be perfect out of the gate. What encouraged them to keep going—even imperfectly—was, as Beverly put it, the realization that “We just need kids to be doing math. We need kids to be thinking and trying to solve problems for themselves and talking to each other about the math instead of just talking to us about the math. If they’re doing math, then it can’t be bad, right?”

Several years into their implementation, they estimate that about 80% of student work is now done on the boards. Observations made while students work at the boards help Beverly and Rachel determine when to provide targeted, small-group work to address specific skills or understanding. Otherwise, their students are up and moving and engaging in math.

Getting others on board

I was impressed with Beverly and Rachel’s willingness to embrace the challenge of overhauling their approach to teaching math. However, I wondered whether their enthusiasm was initially shared by others, particularly administrators, parents, and students. How did each of these groups react to this novel approach?

Thankfully, Beverly and Rachel have administrators who give them freedom to try new things, as long as they can show results. In terms of parents, most had more questions than concerns, so Beverly and Rachel worked hard to develop a clear and effective rationale for why they were moving in this direction. The fact that relationship-building is a key focus in the district helped establish the trust needed to pursue this new approach. And, of course, the results of this approach, which I highlight later in this post, clearly justify the shift to this style of teaching and learning.

Getting students to take the leap

Getting administrators and parents on board is critical, but what about students? How did they react to learning math in a way that was so different from how they had learned it previously?

Beverly and Rachel said students’ reactions have varied from year to year. While they keep procedures and expectations the same for each succeeding class, they have found they need to experiment with how to communicate and collaborate with each unique group of students. Not surprisingly, the students most heavily impacted by COVID were the most resistant to this highly collaborative approach.

Beverly and Rachel also found that, in general, the students at either extreme of the achievement spectrum tended to be the most hesitant: the high flyers just wanted to whip through all the problems quickly, and the kids who were having difficulty just wanted to hide and engage in mimicking behaviors. The beauty of Liljedahl’s approach of having small groups of students working at the vertical non-permanent surfaces is that you can’t hide. High-achieving students need to explain their thinking, which, as Beverly pointed out, can be hard for them; they may know how to do a problem but not how to explain it. And for the students who wanted to fly under the radar, well, there’s no hiding in a group of three.

Building trust through relationships and mindset

Beverly and Rachel identified building relationships and developing growth mindsets as critical components of getting students to trust this approach. As previously stated, relationship building is a school-wide priority embedded in everything they do. Staff take care to personally greet students and one another. Students stay with the same teacher all day for all subjects and loop with them for two years. According to Rachel, they spend time at the beginning of each year talking about growth mindsets and fixed mindsets as well as learning how to negotiate differences. Both are critical components of group work and collaboration.

The nature of the approach itself helps educators address issues head-on. When the teacher is observing and questioning students rather than being the “sage on the stage,” it frees them up to be able to see and address issues and behaviors in the moment. Beverly explained how, “Walking behind the kids, listening to them talk really helps us to be able to go up to a group, listen, and then be able to redirect or give them some help with that cooperation factor.”

Gauging impact: Getting students’ perspective

In preparation for their Fusion presentation, Beverly and Rachel filmed a small group of their eighth-graders reflecting on this approach to learning math. Their comments highlight how Beverly and Rachel transformed their students from passive recipients to engaged, collaborative, and curious pursuers of mathematics. When asked what it’s like to learn math this way, one student replied, “Before, I wasn’t focused on actually learning. I was just focused on getting the whole problem set done…. I wasn’t focused on actually understanding it.”

Students also discussed how this approach changed their beliefs about making mistakes. Previously, a student said they saw making mistakes as meaning, “I suck at this. I’m never going to get this. I might as well just give up.” After learning this way, the students came to see mistakes as just another way to learn. They expressed feeling more curiosity about math and about noticing a change in their mindset regarding math, with one student commenting, “If I set my mind to it, I know I can do it, no matter how hard it is.”

The data tells a story

The student video documents how the thinking classrooms approach changed their attitudes toward math. But did it increase their learning?

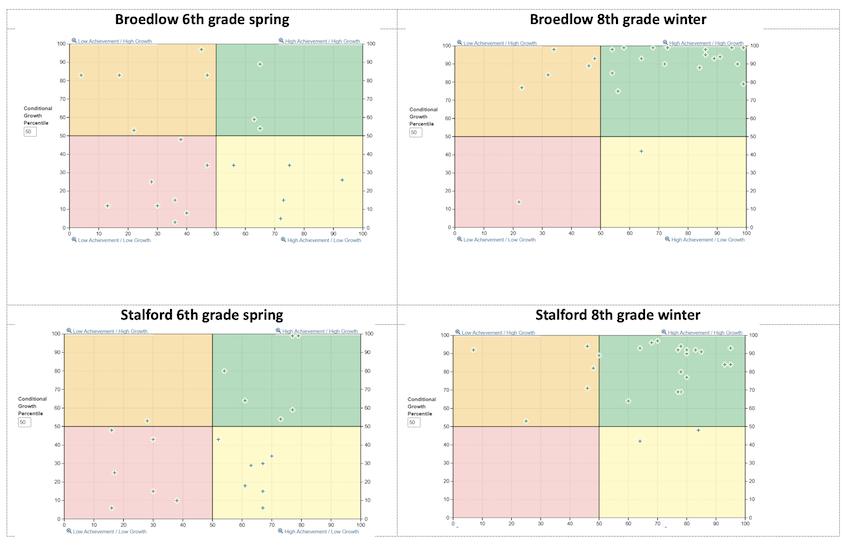

One of the things that was so striking about Beverly and Rachel’s Fusion presentation was the amount of growth their students demonstrated. The quadrant charts from the MAP Growth Achievement Status and Growth report below show their classes’ growth and achievement in math from spring of sixth grade, before they entered the two-year loop with Beverly and Rachel, and from winter of eighth grade, after a year and a half of working in a thinking classroom. As a reminder, the X axis on the chart represents the conditional growth percentile and the Y axis represents the achievement percentile.

Although there were some small changes in class composition over this period, you can see that when they came in as seventh-graders, students were distributed across all four quadrants of growth and achievement. However, by winter of eighth grade, all but two students in each class had moved to the high growth portion of the chart, and in each class over 75% of students were in the high achievement portion.

Although there were some small changes in class composition over this period, you can see that when they came in as seventh-graders, students were distributed across all four quadrants of growth and achievement. However, by winter of eighth grade, all but two students in each class had moved to the high growth portion of the chart, and in each class over 75% of students were in the high achievement portion.

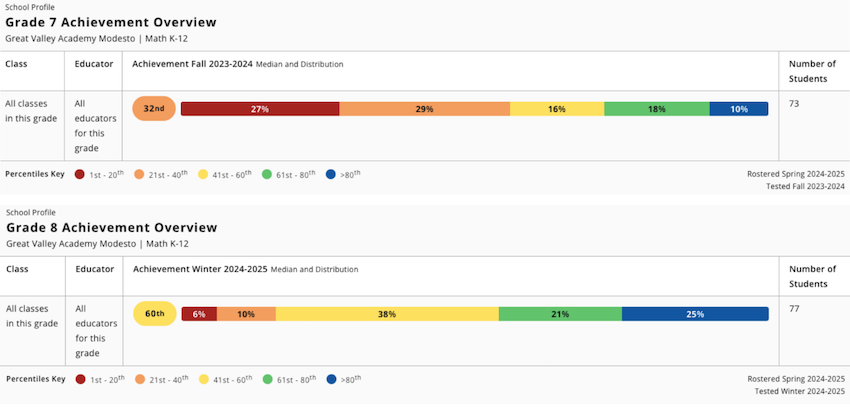

The MAP Growth School Profile report for the same cohort tells a similar story. The students’ median achievement percentile in the fall of seventh grade was the 32nd percentile. By winter of eighth grade, the median had risen to the 60th percentile.

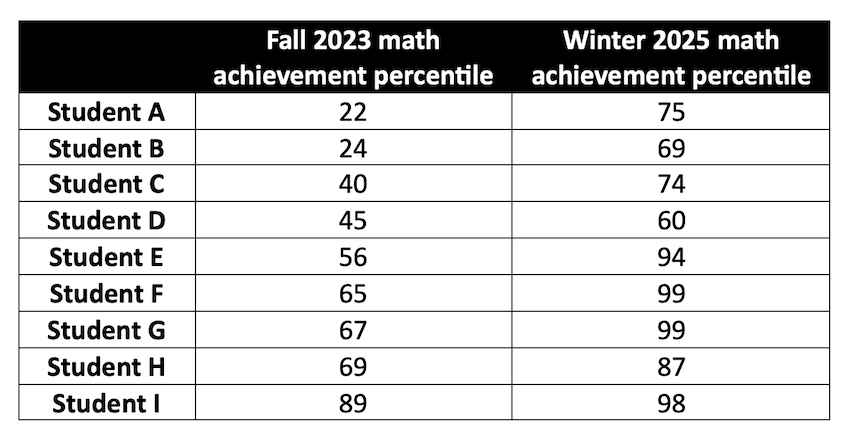

In the video, students also shared the change in their achievement percentiles between the fall of seventh grade and the winter of eighth grade. As you can see from the table below, these changes were significant across all achievement levels.

In the video, students also shared the change in their achievement percentiles between the fall of seventh grade and the winter of eighth grade. As you can see from the table below, these changes were significant across all achievement levels.

More than just numbers

More than just numbers

Beyond achievement and growth data, Beverly and Rachel noted improvements in other outcomes: Attendance and engagement increased among some chronically absent students. Many students who came in thinking they hated math realized that they simply hadn’t truly engaged with it before. And students became eager to work on the vertical, non-permanent surfaces and complained when that wasn’t part of the day’s plan.

The thinking classrooms approach ultimately helped deepen students’ conceptual understanding. The Great Valley Academy curriculum frequently utilizes multipart problems but, often, they found students arrived at the thinking and conceptual understanding expected from completing all parts of the question after they had completed just the first part.

Challenges to using this approach

Given the shift that is required to implement Liljedahl’s strategies, I was curious what Beverly and Rachel found challenging about running a thinking classroom. Here are a few difficulties they highlighted, along with ways they tackled them:

- Translating curriculum into thinking tasks. Beverly and Rachel cited finding meaty, engaging thinking tasks as their biggest challenge. In addition to Boaler’s mathematical mindset tasks and high-level thinking tasks from their curriculum, they found other resources online. A Facebook group provided not only a forum for chatting with other educators at various stages of implementing these practices, but also a spreadsheet of shared tasks and resources. They also used AI to help build tasks and explore how to unpack big mathematical ideas.

- Fitting it all in. As every teacher knows, getting through your curriculum can be a challenge. Although Beverly and Rachel continued to use the district’s required curriculum, they now determine what big concepts their students need to understand and then sequence the curriculum to best support this learning. This involves digging into each lesson and weeding out “the fluff.” Flexibility is key, and they noted that being so in touch with what their students were doing helped them identify what each needed in the moment. Sometimes they would realize at the end of a unit that they needed to circle back to dig into a particular concept, which involved finding or developing a task to support that. Other times they could skip parts of the curriculum as it was clear students had already developed the desired understanding.

- Getting used to “organized chaos.” Beverly described how a thinking classroom looks and sounds in this way: “It is never silent in that room. There are kids moving around, there are kids talking, there are kids hollering at each other across a board. There’s a lot going on.” While she isn’t bothered by this type of classroom, she recognizes that this can be challenging for other teachers. Her advice? Let go of the illusion of control and move away from the traditional expectations of what teaching looks like. This is not the old “I do, we do, you do” approach; it is messy and loud, and to embrace it you have to be willing to release some power and control to your students.

- Making sure all voices are heard. When students go to the vertical non-permanent surfaces, some may naturally dominate, others may not want to speak up, and still others may not fit into their group for some reason. Building relationships, trust, and community is key to getting students to engage in deep mathematical thinking together. Beverly and Rachel spend time training the class to be inclusive and supportive. They also address these types of community issues in real time, for example, by encouraging a student who is dominating a group to be the silent scribe so others can speak. They have also implemented a collaboration rubric where students self-assess on how they collaborated, whether they got distracted, and if they engaged more with another group than their own.

What makes it worthwhile?

I wrapped up by asking Beverly and Rachel what they each liked most about the thinking classrooms approach.

Rachel noted that she appreciates how it helps students build collaboration and communication skills and how it drives them to think deeply. For herself, she appreciates how having the students engage in this way takes the pressure off the teacher and places the emphasis on student reasoning. When she looks at their works on the vertical non-permanent surfaces, she sees how the students “are doing more math in a day than they’ve traditionally done in a week or two weeks.”

For Beverly, the volume of math that students engage in is incredible, as is the pride they take in realizing how much math they have done and how their understanding has grown.

Just do it!

Hopefully, Beverly and Rachel’s success—and the incredible growth of their students—has inspired you to move toward implementing a thinking classroom in math.

Still not sure how to get started? Rachel advises others to try the same approach she and Beverly used: “It doesn’t have to be perfect; you just have to start it. If you start somewhere, it gets better over time. You get sharper with the tools by just trying one thing, and then trying another thing, and then continuing on and on until you have the full thinking classroom.” You can also heed Beverly and Rachel’s students’ advice to students shifting to learning math this way: don’t be afraid to ask questions, have a growth mindset, and trust the process.

To learn more about building a thinking classroom of your own, I encourage you to read my previous post and Liljedahl’s book. For more on how MAP Growth can help you understand where students are in their learning, visit our website as well as the archive of posts on MAP Growth here on Teach. Learn. Grow.