Neat rows? Always. Groups of five? In June, if ever. As far as variety in student grouping for cooperative learning goes, my experience as a student in the ’90s was pretty limited.

There was an obvious rationale when I was a kid: you sat next to those whose names came before and after yours in the roll book because alphabetical order was tidy and easy. I became lifelong friends with some Bs and Ds, but I often wonder what could have been had the Cs been able to mingle with the Rs. Now that I’m an educator myself, I realize that when left to chance or, in the case of my school years, alphabetical order, the possibilities for student collaboration and growth become limited.

My teachers, though seasoned educators, didn’t step too far outside the seating box. They were products of their times. Today we know that a dynamic classroom environment empowers learners. Jonathan Ryan Davis, a professor at The College of New Jersey, refers to this as “a re-conceptualization of classroom management.” I suggest we go a step further and pair re-conceptualization with intentional grouping, a research-backed strategy for supporting student growth studied by my colleague Chase Nordengren as part of our High Growth for All project.

A bit about our High Growth for All project

Chase’s research on effective teaching strategies uncovered ten in particular that can help educators make the most of their instructional time. We are calling these the Transformative Ten:

- Provide supplemental learning time for targeted retrieval practice

- Mix whole-group, small-group, and individual activities

- Adjust student groups in real time

- Share students and strategies within a grade level

- Differentiate tasks within a unit

- Provide targeted practice for foundational skills

- Teach from multiple standards at once

- Create opportunities for self-directed learning

- Use student discourse as formative assessment

- Explicitly teach academic vocabulary

While some of these may see obvious, until Chase embarked on this research, worked closely with educators every step of the way, and eventually put pen to paper, these principles existed mainly in the edu-ether. His exploration and distillation of practices many of us already use can help educators more effectively provide grade-level instruction to all students, while differentiating as needed.

I’ll be focusing on cooperative learning in this blog post, the second Transformative Ten strategy. It calls on us to mix whole-group, small-group, and individual activities, and my aim is to help you know when to do which and how to use each approach effectively. I encourage you to also learn about the research and all the strategies on our High Growth for All website and read our Transformative Ten practices guide.

Step 1: Set clear goals

When you begin to think about cooperative learning, I recommend you establish a clear goal. What is your intention when using groups? Is it to promote more productive conversations? Is it to allow students to showcase certain skills? The answer, to both of those questions, should be yes.

Next you’ll want to think about how to make groups function at a high level. Start by looking at your scope and sequence. Where you are in the learning matters. Sending students off in a small group or in pairs might not work at the beginning of a new unit, for example, so ask yourself, what works best for where we are right now?

I think it is also important to confront any discomfort you might understandably have about dynamic classrooms. Asking questions like the ones that follow can help you prepare for the reality that some friendly group conversations may lead to unfinished learning, which you’ll need to address.

- Am I comfortable with the groups occasionally going off topic?

- How important is ensuring all groups have a certain outcome?

- What activity do I have planned to summarize the learning?

Student groupings without clear expectations and outcomes will almost certainly lead to chaos. While a dynamic classroom can appear to be chaotic, the key to its success is intentionality. Setting clear goals will help you start from a firm foundation.

Step 2: Put data and observations to work

Once upon a time, we used to think about grouping as either hetero- or homogeneous, based on ability and instructional level. I challenge you to expand that definition and think of groupings as intentional. Whatever combination you choose for a group, a topic, or a marking period, make sure it is data-driven and capable of creating the conditions for success. Information about your students is all around you. Look to it when making student grouping decisions.

When I was teaching, my classroom was open to visitors and observers daily, so I had to be ready to discuss not only lesson content but my differentiation and grouping rationale, too. I would look to everything I knew about my students when making decisions. I would consider formative assessment data, from things like entrance slips on a Monday morning. I would refer to diagnostic data, like unit exam scores, but also interim assessment performance. (My school used MAP® Growth™, so I would focus on RIT scores and bands, displayed on reports like the Class Breakdown by Instructional Area.) I would also consider my observations of student friendships and dynamics, plus one-on-one conference notes. All of these things, when looked at holistically, helped guide my decisions around cooperative learning.

Step 3: Consider different configurations

Group work can take a few different shapes: whole group, small group, and pairs. Some work is best done individually.

Whole group instruction is the tried-and-true method of classroom grouping simply because it works most of the time. When you are starting a new topic, when you want to create a cohesive vision, when you want to get everyone on the same page, whole group just works. Whole group instruction does not mean that we ignore all the ability levels in the classroom, however. It just means that we have decided that a lesson, or a moment in a lesson, is appropriate for all levels.

What I love about whole-group instruction is the sense of unity it creates. We all enter a moment of new learning together, as a class family. It is great to help students feel that their learning is bespoke to them, but it is equally important for them to feel like a valuable member of the whole. Whole-group instruction is also an excellent opportunity to model academic thought, metacognition, and discourse. I love taking that time to think aloud, brainstorm, plan, and convey to students that inquiry is a necessary part of the learning process.

When to use whole-group instruction: When the benefits of having everyone involved won’t isolate students at different levels and prevent them from feeling valuable and contributing.

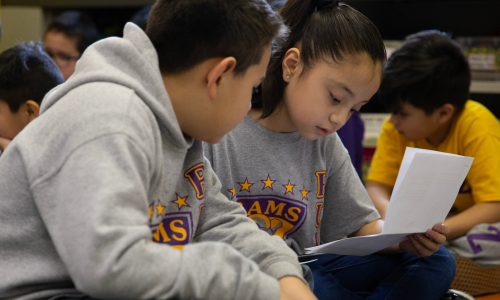

Small groups, typically between three and six students, are common in most classrooms today. This could be due to the frequent departure from rows to a more communal classroom environment. Small groups naturally promote discussion, which comes with its own challenges and triumphs.

If you’re an elementary teacher and juggle multiple subjects a day, I encourage you to look at dynamic small groups as a way to signal the transition from one subject to another. After all, your data will probably affirm that students rarely remain static in their achievement and level from subject to subject.

Teachers of older kids can allow for student choice in groupings if the activities are differentiated to support the students’ various levels. When I was a middle school teacher, I would occasionally permit my students to select their own groups from a choice of four. I made sure that regardless of their decision, however, the tasks at each group provided multiple entry points. While I used this more casual style of grouping less frequently, say, before a holiday, a dynamic classroom culture and high expectations maintained the integrity of my lesson. We had fun, too!

When to use small groups: When a conversation or activity would benefit from a small number of students with varied levels of expertise.

Using the same foundation as small groups, pairing opens students up to sharing in half of the ownership of a project or discussion.

I liked to pair some of my emerging math students with their classmates who possessed not only sound understanding of a concept but also the empathy needed to foster productive collaboration. Pairing students of similar levels serves when you want to reduce hesitation because similar levels even out the playing field and make routine practice more useful.

When to use pairs: When the goal is to have both students benefit from concentrated collaboration.

Sometimes, students need the space to think and learn on their own. While whole group is great for creating a theme or introducing a topic, and small groups and pairs promote discussion, sometimes the quiet of one’s mind is best. Think of individual work time as providing a meditative moment, where students can withdraw from the noise of the class and work in a space most comfortable to them.

Ten years ago or so, a “successful” classroom was a noisy one. Students had to be in groups, at the board, or in the hall to appear to be actively working and successful in their learning. The key word here is “appear.” Without systems in place to evaluate learning goals, these classrooms were often more razzle-dazzle than successful, and the chaos didn’t enhance learning or help students meet objectives. The takeaway from that movement was the (triumphant) return of individual practice time. Teachers began to see the need for and value in balance between intentional groups and time for students to practice on their own.

In many ELA classes, you’ll observe students participating in independent reading or writing time. It’s a quiet time planned into the week where students can work at their own pace on their own work. I’ve extended this practice to math, too.

To make the most of this groupless configuration, you should model metacognition and academic thought for your students first. They need to learn about that from you and be familiar with the internal dialogue needed to be a quiet critical thinker first.

When to have students work independently: When a quiet moment to reinforce skills or to work at a more comfortable pace, without the pressure of another voice, is necessary.

Step 4: Understand your role

While the teacher is seen as being front and center during whole-group instruction, you’re also modeling conversation and teaching your students that their feedback and participation should be routine and that both are expected. When students are working in small groups, pairs, or individually, you can wear several hats, such as facilitator, coach, or thought partner.

Many teachers set up a desk for themselves with a group so they can really embed themselves in a discussion, observe the group dynamic, and elicit feedback from their students. These observations can serve as another data point you can triangulate with your formative and summative data when planning more cooperative learning opportunities in the future.

Pairing in particular lets you zoom in a bit more closely without feeling like you’re having a conference with a student. Having one other student present reduces intimidation for a lot of kids, while also helping them avoid feeling that the eyes of the crowd of a small group are on them.

When students work independently, take this moment to conference or spiral in topics specific to that student’s needs, based on the most recent data you have for them.

Before you go

Whichever method of grouping you choose during cooperative learning time, mix it up. During your weekly planning, try to incorporate as many different grouping styles as are suitable for that week’s learning. Here are a few additional things to keep in mind:

- Students can be startled by novelty. If changes to your classroom groupings happen infrequently, transitions could unintentionally create distraction that does more harm than good. So, the earlier in the year you begin using dynamic groups, the better.

- Don’t feel pressured to try all types of student groupings all at once. Some weeks will naturally lend themselves to more creativity than others.

- If something doesn’t work, learn from it. There will be times when a lesson just doesn’t go the way you’d hoped. Consider that data that can inform what you avoid next time around. Trust me when I say that you won’t break the profession or cause years of learning loss if you went with pairs when whole group may have been the better choice. Give yourself grace.

Neat rows sure look great, but there is no reason we should cling to that old model too tightly for fear of chaos. Considerate, deliberate planning will reveal the difference between intentional chaos and just chaos.

For more on our High Growth for All project and the Transformative Ten instructional strategies, watch our video on student grouping, read our guidance document on student grouping, and listen to our The Continuing Educator podcast episode on differentiation.