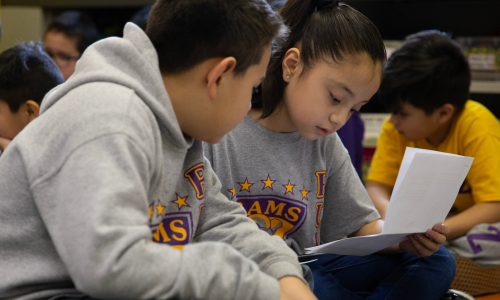

Who has better reading comprehension of a text, the student with “advanced reading skills” or the one who has a wealth of knowledge about the topic?

If you’re familiar with the Baseball Study, then you know this is a simple question with a complex answer—and important implications for how we understand learning and literacy. This study, conducted in 1987, found that having more background knowledge in a specific topic can be more predictive of a student’s success in comprehending a written text on that topic than having a high score on an overall reading comprehension test.

In the academic setting, we often call background knowledge a “shared academic vocabulary,” and it’s such a critical component of reading comprehension—and learning overall—that NWEA included the teaching of academic vocabulary as one of the Transformative Ten strategies that can be found in some of our nation’s highest-performing schools. These strategies emerged from High Growth for All, an NWEA research project that examined instructional practices in a handful of the country’s highest-performing schools.

Here are a few tips for making better use of the simple but powerful practice of teaching academic vocabulary to improve reading comprehension and achievement.

1. Keep word lists front and center

To succeed with grade-level content, students need a basic set of tools for approaching and understanding the curriculum in front of them—and this includes subject-specific academic vocabulary that helps them feel informed, up to speed, and ready to learn. Whether you’re teaching literature or mathematics, creating word lists and making them readily available to your students will greatly increase their preparedness for new material.

And it’s not just students who benefit from word lists. You, too, can use them as reminders to use the terms regularly yourself and avoid taking your own background knowledge for granted. We all fall back on our own speaking patterns, which may or may not be helpful to students as they work toward specific learning goals. By creating—and continuously referring back to—word lists that are explicitly connected to the concepts you’re teaching, you can help put your students on a level playing field where it’s your efforts to build a shared academic vocabulary, rather than students’ individual background knowledge, that determines their outcomes and growth.

2. Embrace teachable moments

In the High Growth for All project, NWEA researchers found that the most effective teachers make a habit of creating specific opportunities for students to learn new vocabulary terms. In humanities and mathematics alike, these teachers regularly focus on introducing new words that will allow students to actively participate in all the conversations and academic exercises to follow.

Sometimes, however, learning opportunities arise outside of the structured spaces planned by teachers. When students come across a word they don’t know—whether they bring this to your attention themselves or you simply intuit that there’s something they’re not grasping—take a minute to pause and assess. Take these gaps in understanding seriously, as even a single word could be critical in helping students successfully interpret a text or complete an activity. You might be on a roll with your lesson plan, but these little interruptions represent teachable moments that you can use to your advantage by discussing a word’s meaning and adding to your prominently displayed word list.

3. Make the most of morphemes

Because it’s easy to get overwhelmed by the sheer number of words in the English language, breaking them down into their functional and meaningful parts—or morphemes—can help make vocabulary instruction a more manageable process with plenty of “aha” moments.

For example, a student may never have seen the word “intractable,” but if they learn that the morpheme “tract” means “to pull,” then they can infer the meaning of “intractable” to mean, roughly, “you can’t pull it.” In this way, understanding morphemes can help open a lot of doors for students who may not be familiar with certain words but know where to look for clues as to the words’ meaning.

As Margaret McKeown, senior scientist and professor emerita at the University of Pittsburgh, explains in a short video on early vocabulary development, “Morphology is one of those resources where if you’re familiar with word parts, whether they’re prefixes, suffixes, or roots … those can help you either infer the meaning of a word, or they might help you figure out the pronunciation of a word that you might realize, once you’ve said it to yourself, you actually know! But you just didn’t recognize it in print.”

4. Encourage curiosity about words

One of your best assets in the effort to expand the way you teach academic vocabulary is the natural curiosity that kids bring to everything they do. You can tap into this curiosity and get kids interested in—even excited about—the new words they encounter as they approach new subject material.

Along these lines, I highly recommend keeping a tab open for the Online Etymology Dictionary, a website that’s a lot more fun and engaging than its name might suggest. Simply type in any word, and you’ll get a solid explanation of where the word originated, why it’s spelled the way it is, and what other words it’s related to.

It’s not always easy to make sense of the English language (consider the different pronunciations of “though,” “through,” “cough,” and “rough”), but the goal here is not to solve every mystery but, rather, to encourage and reward curiosity. Research suggests that nurturing curiosity in this way can have a major impact on what students are able to comprehend. And with the right resource at your fingertips, you can always respond to students’ questions about particular words with, “I don’t know. Let’s look it up together and find out.”

It starts with you

Because we can’t expect students to understand words that we don’t actually use ourselves, the critical first step in teaching academic vocabulary is simply to model the vocabulary we need them to know. Your students might think you put that big word list on the wall for them, but it can be just as valuable a resource for you. And with these vocabulary terms front and center, you can then tap into professional development resources to strengthen your pedagogical practice.