How can we efficiently meet students where they are and provide student-centered mathematics instruction based on appropriate and high expectations? Spoiler alert: There is no easy answer. And we should be exceedingly cautious about one possibility: tracking students by math ability.

Tracking doesn’t add up

Many of us grew up in a time or place where we were at some point separated and sorted for mathematics instruction. I’m not talking about some students going to first hour and some to second hour. I’m referring to sending students, such as middle school students, to different types of math classes. Some students were sorted into low-level classes, others into high-level classes, all based on a perception of student ability. It’s a practice known as tracking.

In recent years, though, researchers have studied the impacts of tracking students by math ability. The results, which provide reasons to question the assumption of its efficacy, are reflected in the 2020 Washington Post article “Is it time to stop segregating kids by ability in middle school math?” The article tells the story of Ithaca City School District, in New York, and their decision to stop the practice when educators there noticed it didn’t appear to be working to anyone’s benefit.

Ithaca certainly wasn’t the first to rethink tracking. In 2014, San Francisco Unified School District ceased the practice of tracking middle school mathematics in a decision supported by research. Their results show that detracking works remarkably well and has resulted in more students taking higher-level mathematics classes.

These aren’t the only instances of questioning the practice of tracking. The National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics (NCSM) released this bold statement on tracking: “As a practice, tracking too often leads to segregation, dead-end pathways, and low quality experiences, and disproportionately has a negative impact on minority and low-socioeconomic students. Additionally, placement into tracks too often lacks transparency and accountability. Overall, tracking does not improve achievement but it does increase educational inequality. In light of this, NCSM calls instead for detracked, heterogeneous mathematics instruction through early high school, after which students may be well-served by separate curricular pathways that all lead to viable, post-secondary options.”

Reconsidering tracking

Despite some districts bravely moving away from tracking, the practice is widespread. Tom Loveless, in a 2016 study for the Brookings Institution, noted that for grade 8, “the average state tracked about three-quarters of its math students.” And, while there is debate as to what benefits tracking may provide—and to whom—there is enough evidence to warrant being exceedingly cautious about tracking, questioning its impacts, and recognizing the power it has to block student access to mathematics.

Tracking almost certainly has the ability to reinforce inequity in education. In the 2019 Branching Out report from Just Equations, authors Phil Daro and Harold Asturias connect the sociological Matthew Effect to mathematics learning. This notion, wherein the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, illustrates how gaps widen over time. It truly provides an apt metaphor for tracking: “Perhaps the most obvious and cruelest example of the Matthew Effect is the failure to offer all students a realistic opportunity to learn the mathematics needed for advanced high school courses, then tracking the same students away from those courses because they are assessed as lacking the mathematics they never had a chance to learn. Tracking doesn’t solve the failure to prepare many students. It multiplies the damage.”

If your school tracks students, or plans to do so, I hope you can address these questions fully and honestly:

- Do you study disaggregated long-term impacts on students?

- Do you know which students are disproportionately tracked into lower levels?

- Is the placement of students into tracks accurate and proven?

- Do the methods of placement justify blocking opportunity and the resultant long-term impact it will have on students?

- How easily can students switch tracks? How often does it happen?

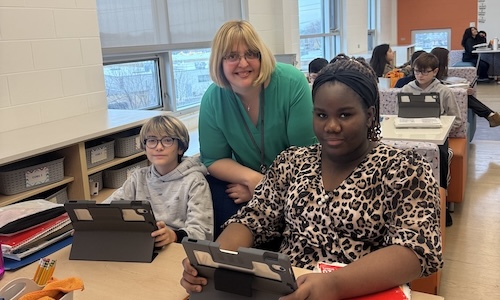

You’ll likely realize it would be best to avoid tracking. Try heterogeneous grouping instead. This form of grouping requires meeting individual students where they are. Teachers can also strategically use tools, such as MAP® Growth™ and MAP Growth instructional connections, to facilitate differentiation. Not tracking may not be the easiest path, but it will very likely be the best one for students.