A few years ago, NWEA designed content-focused professional learning on math and literacy. As part of developing the work, I attended a math workshop with Scott Adamson. It was one of the best professional development sessions I’ve ever attended. It was challenging and thought-provoking and not at all the “sit and get” type of workshop that I had attended so many times as a teacher.

A few years ago, NWEA designed content-focused professional learning on math and literacy. As part of developing the work, I attended a math workshop with Scott Adamson. It was one of the best professional development sessions I’ve ever attended. It was challenging and thought-provoking and not at all the “sit and get” type of workshop that I had attended so many times as a teacher.

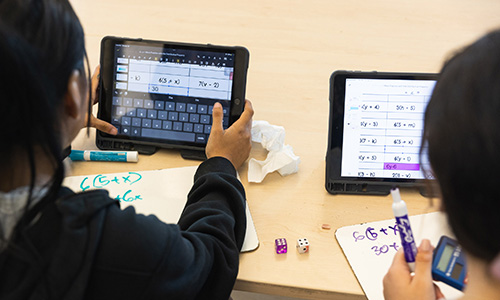

Scott had us standing up in groups of three at what he called “vertical non-permanent services,” essentially chart paper–sized whiteboards. He posed a series of questions for us to work through. Challenging questions. Non-routine questions. He gave us dry-erase markers and set us to work on our whiteboards.

Initially, the work was daunting; some of the questions really pushed our mathematical knowledge, which was a little unnerving. We had deep discussions in our groups about how we could unpack and tackle these problems. All the while, Scott circulated around the room, asking us about our thinking and our approaches to the solutions. He encouraged us to consider other groups’ work relative to our own. Overall, it was engaging, intense, and exciting, and in the debrief afterward, it was clear that few of us had experienced math in quite this way before.

What’s going on in math class?

What I didn’t know at the time was that Scott was using principles from Peter Liljedahl’s book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Grades K–12: 14 Teaching Practices for Enhancing Learning. After attending the workshop, I immediately moved the book to the top of my to-read list and was not disappointed by what I discovered.

In the book, Liljedahl, a professor of mathematics education at Simon Fraser University and former high school math teacher, details 14 teaching practices for enhancing mathematical learning. The work was born out of a series of observations Liljedahl made in 40 math classrooms in 40 different schools. Regardless of the grade (he visited K–12 classrooms), socioeconomic status, or whether schools were public or private, Liljedahl noticed that students were not thinking in math classrooms. Were they doing the work assigned to them? Sometimes yes and sometimes no, but either way, that did not always equate to thinking.

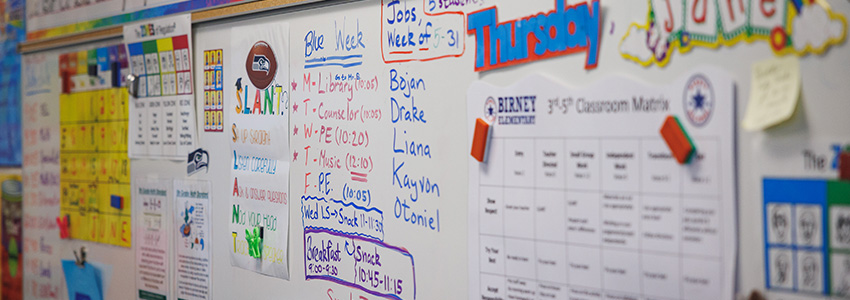

Liljedahl outlines five behaviors that he observed students consistently engaging in:

- Slacking. These students do not attempt the task at all and don’t hide that fact.

- Stalling. These students also do not attempt the task but are more subtle about it. They spend time off task doing things like sharpening their pencils or getting a drink.

- Faking. These students pretend to do the task but mask not doing it by stalling in a way that appears more academic. They flip through a textbook or look like they are thinking deeply but produce no significant work.

- Mimicking. While this group of students do attempt the task, they are mostly just mimicking what the teacher did rather than building understanding of their own. If the problem varies in any way from the teacher’s demonstration, they are lost.

- Trying on their own. These students are actually doing what any teacher hopes all students will do: engage with the problem and persevere in solving it.

Liljedahl estimated that in his observations, only about 20% of students were engaged in the desired behavior of trying it on their own, and nearly 30% of students were either slacking, stalling, or faking. The remaining approximately 50% were “doing the work” but they weren’t thinking. They were just following the rote path laid out by the teacher.

A need for change

Based on these observations, Liljedahl set out to determine what actually gets students actively thinking in math class. He started by noting how similar most classrooms are: tables or desks are pointed toward a designated front of the room where teachers lead students through activities on a vertical writing space. Students typically work on a horizontal writing space. Most classes followed the “I do, we do, you do” model, which resulted in the non-thinking and the behaviors detailed above.

Next, Liljedahl spent 15 years working with over 400 K–12 math teachers to find what strategies both increased the number of students actively engaged in thinking and the amount of time they spent thinking. The results are the strategies highlighted in the book.

The structure in Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics

Beyond the wealth of knowledge contained within, one of the things I appreciate most about Liljedahl’s book is the way it is structured. Each chapter tackles one of the 14 teaching practices in depth and is organized with a parallel structure, making unpacking and understanding each strategy easier. The final chapter gives advice on how to implement the 14 practices by grouping them into a framework of four toolkits, or clusters of practices.

Each chapter begins by discussing “The issue,” or a commonly used teaching practice that will be replaced by the chapter’s strategy. Liljedahl then goes on to unpack “the problem” with the commonly used approach. He then transitions to the topic of the chapter, which is the strategy that builds “toward a thinking classroom.” Each chapter ends with comprehensive FAQs, a summary of the micro and macro moves you can make to enact the strategy, questions to think about if you are reading the book with a PLC, and a “Try this” tips and tricks section designed to help you get started with the strategy.

Interwoven throughout each chapter are examples of tasks and interactions from classrooms as well as images, illustrations, and research citations. The book’s companion website also provides a variety of free resources, including numeracy and thinking tasks, a book study guide, and an executive summary of each chapter.

Getting started

As stated above, Liljedahl recommends the ideal way to move through his book and implement the practices. I will not attempt to discuss all the practices but will touch upon the three I experienced in the workshop and which happen to form the first of the four toolkits.

Types of tasks that encourage thinking

The first strategy Liljedahl focuses on is, to me, the most critical: the mathematical tasks we give to students.

Liljedahl distinguishes thinking tasks, or true problem solving, from what he calls curricular tasks. True problem solving is “what we do when we don’t know what to do.” As he describes it, “Good problem-solving tasks require students to get stuck and then to think, to experiment, to try and to fail, and to apply their knowledge in novel ways to get unstuck.” By contrast, curricular tasks are those where students know what to do because the solution path has been laid out for them in the “I do” and “We do” sections of the lesson.

Liljedahl identifies three types of tasks that encourage thinking and true problem solving:

- Highly engaging thinking tasks. These tasks are so juicy and enticing that you can’t help but engage in thinking.

- Card tricks. These are not sleight-of-hand based but, rather, card tricks that are built on and can be explained by math.

- Numeracy tasks. These are rich, ambiguous, open-ended tasks grounded in real-life contexts relevant to students.

By their nature, these three types of questions support engagement, encourage dialogue, and help students develop a deep understanding—and dare I say enjoyment—of mathematics. That said, they may not directly correlate to your curriculum, which could be a stumbling block for teachers and administrators. However, Liljedahl details how to reverse engineer a more typical curricular question to make it a true problem-solving experience. It starts with asking a question that engages the students’ prior knowledge, followed by asking a question related to your curriculum, which extends that knowledge. Finally, students are asked to do something they haven’t been taught to do yet.

Interestingly, Liljedahl found in his research that engaging students with one of the three types of tasks that encourage thinking before working on a more traditional curricular task increased the amount of thinking students did, even with the more traditional curricular task. His conclusion was that when students start off thinking, it primes them to continue to do so, even when presented with tasks that previously encouraged mimicking.

Forming collaborative groups

This chapter resonated deeply with me because it reminded me of how much time and thought I put into forming student groups when I was in the classroom. The questions I asked myself are likely ones that many teachers have wrestled with:

- How should I structure the groups based on students’ degrees of understanding?

- When do homogenous groups make sense? When do heterogenous groups make sense?

- How can I balance groups appropriately to make sure all students are engaged and have a voice?

- Which students can absolutely, never, ever be in the same group, for a variety of reasons?

Liljedahl boils all this down into the three things teachers typically think about when forming groups:

- Pedagogy. This approach focuses on forming homogenous or heterogenous groups based on how you think students will learn best.

- Productivity. When productivity is the priority, you form groups based on what you think will improve or increase work output based on students’ leadership or collaboration styles.

- Peacefulness. Student dynamics can play a role. When that’s the case, you likely form groups based on social considerations to improve productivity and/or reduce disruption.

Despite all my thinking and best intentions, I struggled to consistently form effective groups. Amazingly, Liljedahl puts forth a far simpler method that produces more effective results: randomly, transparently, and frequently grouping and regrouping students into sets of no more than three students. He suggests having students pick cards and forming groups based on the number drawn or using a free online random group generator.

However you approach grouping, do it efficiently and frequently (every hour or so) and make sure students can see (and, therefore, trust) that it is truly random. What does all this randomness do? Liljedahl found that forming small, visibly random groups shifts the dynamics and elicits more active thinking from all members. Students are less likely to default to typical roles of being active/dominating or passive. When grouped in this way, students are more open to collaboration and knowledge sharing.

Liljedahl also gives tips on how to troubleshoot issues, like when those two students who should absolutely, never, ever be in the same group wind up being placed together.

Using vertical, non-permanent surfaces

The final strategy in the first cluster of practices in Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics is the chart paper–sized whiteboard we used in our workshop. Based on that experience, I could see that working with those was different from sitting at a desk and working together; there was something more dynamic and energizing about standing up and working at the whiteboard.

Liljedahl spent a great deal of time studying which type of workspace—vertical whiteboards, horizontal whiteboards, vertical paper, horizontal paper, or notebooks—improved various measures related to thinking, including time on task, amount of discussion and participation, and persistence. Vertical, non-permanent surfaces came out as the clear winner, but why? In talking with students, Liljedahl found that when students sit, they feel a sense of anonymity that allows them to more easily disengage.

Whiteboard-based work nearly eliminated stalling and faking behaviors. As Liljedahl puts it, “In the 15 years that I have been engaged in thinking classroom research, nothing we have tried has had such a positive and profound effect on student thinking as having them work in random groups at vertical whiteboards.” From the teachers’ perspective, the vertical whiteboards allow teachers to easily and quickly review each group’s thinking in a way that makes it easier to help move an individual group or the class along.

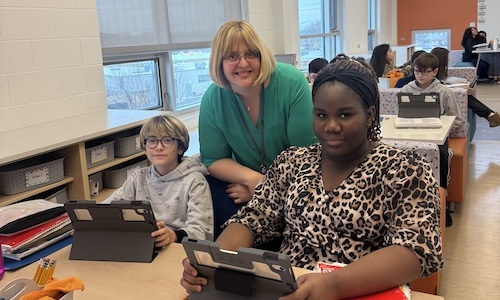

Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics in action

Liljedahl’s book offers a transformative approach to math instruction—one that prioritizes student thinking, collaboration, and engagement. Hopefully this brief dive into Liljedahl’s work has piqued your interest in learning more.

While I regret that I have not had the chance to implement these ideas in the classroom myself, I was excited to meet two educators who have. At this year’s Fusion, NWEA’s user conference, I saw an amazing presentation by Beverly Broedlow and Rachel Stalford, two teachers who implemented these practices in their classrooms with incredible results. Keep an eye out for a follow-up article here in Teach. Learn. Grow., where they share how they implemented these practices as well as the impact they saw on their students’ engagement and academic growth. In the interim, I encourage you to visit our archive of articles on math instruction for more ideas of things you can try in your classroom.