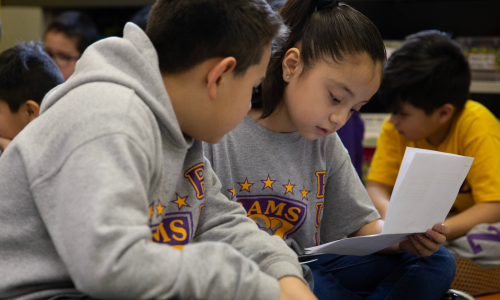

Not like yesterday’s reading class

ELA relies on so much of a learner’s toolkit: reading, writing, grammar, spelling, vocabulary, speaking and listening, speech and debate, poetry and research. With such a robust landscape, we promise to provide equally rich resources.

WEBSITE

How MAP Reading Fluency with Coach supports early readers

Precise student placement, targeted interventions, and personalized 1:1 tutoring—it’s all possible with MAP® Reading Fluency™ with Coach.

GUIDE

How assessment data drives literacy development

To help emerging readers develop their literacy skills, you’ll need more than solid data from learning assessments. Take a look at how teachers are succeeding with practical, research-informed data strategies for supporting their young readers.

WEBINAR

To better understand dyslexia, look to the science

Learn key research findings about dyslexia and practical strategies for helping colleagues and caregivers better understand the most common learning disability.