I want to tell you a story about a shy girl who always had her head in a book. Because she always had her head in a book, no one knew she struggled to read. No one knew how much longer it took her to read a story than the other students. No one knew she didn’t finish standardized tests because she had to re-read the entire passage to answer every single question. Guess what? That shy girl was me, and I have ADHD.

What are executive functions?

What I know now, but didn’t know then, is that reading (and writing!) require a lot of executive functions. Executive functions are the mental skills we use to manage our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in order to achieve goals.

Since achieving learning goals is the primary purpose of K–12 education, our students must put their growing executive function skills to work every single day, in myriad ways. And since people with ADHD often struggle with executive functions, they can benefit from extra support to develop the skills needed for reading.

Turns out that the same instructional strategies that work with kids who have ADHD can help all students free up mental energy to use on tasks like reading for pleasure, reflecting on a book’s theme, and analyzing an author’s argument. This is the kind of flexible reader we want all students to be, and knowing how to support their reading-specific executive function skills is one way to help them get there.

Why are executive functions important for reading?

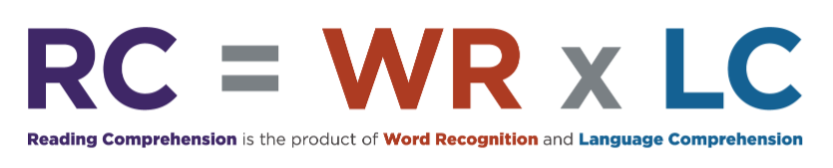

Students have to decode words to be able to read. That’s a given. And they have to know what words mean to make meaning from texts. Another absolute. That’s why word recognition and language comprehension are the two primary factors in the simple view of reading.

You are likely already familiar with Philip Gough and William Tunmer’s simple view of reading. You may also know they didn’t claim this model covers every single mental process involved in reading. We know that motivation, engagement, background knowledge, and (yes!) executive functions all play an important role, too.

Looking back at the simple view, we might consider executive functions to be the brain’s way of coordinating word recognition and language comprehension—the two factors that must happen simultaneously for reading comprehension to occur. An alternative model, the active view of reading, proposes exactly that.

For the purposes of this article, it’s not important that we agree on which model of reading is right or best. My goal is to help you better understand what executive functions are, how we use executive function skills when reading, and how we might best support students in developing them.

So, here are five ways to help students better understand and build reading-specific executive functions.

1. Support planning and organization

Planning helps us all set goals, and organization helps us achieve those goals. In reading, students need to know why they are reading. And they need to know how they should read to achieve those reading-specific goals. Should they skim a text for the main gist? Use headings to locate a piece of information? Re-read a text multiple times for a deeper analysis? Or should they simply enjoy the excitement, humor, or knowledge gained from reading for pleasure?

Knowing about different purposes for reading and different ways to read helps us become more effective planners. Planning becomes especially important as students begin to read more widely and are expected to read longer and more difficult texts. Meanwhile, knowing how texts are organized helps us remember what we read because it gives us a mental structure to hang our hats on—or, in this case, our summaries.

Tips for educators

Here are two specific things you can do to help your class with planning and organization:

Teach students to think more explicitly about why they are reading. What is their goal? What steps can they take to achieve that goal? After reading, have students reflect on how well they did and what they might try differently next time.

Teach students about the structure of language—at the word, sentence, and text level.

Words have inherent structures. Think spelling patterns and syllables, which are often based on roots and affixes. Ask students to find these patterns and word parts in the texts they read, and then work with a partner to list other words with similar patterns, parts, and meanings.

Sentences are made up of words. Learning how words are ordered to make sentences builds syntactic awareness, which we need to become strong readers. Give students a stack of 5–10 word cards and see how many ways they can arrange them into complete sentences.

Texts are made up of sentences. Narrative texts typically have the same structure: a problem, goal, events, and an outcome. Have students work on story maps, first with support and then on their own. As they internalize this structure, they’ll get better at retelling and summarizing stories, too. You can also use story maps to analyze multiple perspectives. Have students note how each character responds to the same events in a narrative. Then have them reinterpret the story from these different points of view.

2. Support developing working memory

Working memory refers to how we temporarily hold onto bits of information until we no longer need them, like where we put our car keys or phone. When reading, we hold onto bits of text until we’ve made the connections needed to understand the text.

One way we use “bits of text” is to resolve writing shortcuts, such as pronoun and acronym use. Each time I connect an acronym back to what it stands for, I use up some of my working memory, which has a fixed capacity.

Our working memory helps us make deeper connections when reading, too. It’s how we integrate each new part of a text into what we already understand of its structure, or how we re-evaluate an author’s argument every time we encounter a new claim or counterclaim.

Tips for educators

To assist kids with developing working memory, try the following:

Show students how to use graphic organizers for reading. Graphic organizers are a great tool for teaching students the structures of informational texts (e.g., compare-contrast, definition-example, problem-solution), which are more varied and sometimes more challenging than literary texts. Graphic organizers can also support inference-making. Record two pieces of information directly stated in a text, then give students a space to speculate about what’s missing. The missing information is the inference, or the meaning that readers must bring to the text.

Show students how connecting words signal the relationship between ideas in a text. Try removing a connecting word (e.g., “because,” “instead”) from a text your students are reading. Next, ask students to visualize what is happening and (literally) draw connections between the individuals, events, or ideas in the text until they know what the missing word should be and why.

3. Support cognitive flexibility

Cognitive flexibility is what allows our minds to shift between one task and another, say when we read an email and listen to a podcast at the same time. When learning to read, students must constantly shift between the tasks of decoding and meaning-making, as explained in this short video. When reading to learn, students spend more time shifting between basic comprehension and deeper critical thinking, such as analyzing an author’s purpose or resolving conflicting evidence across two or more texts.

Tip for educators

When you focus on cognitive flexibility, engage students in activities that require constant shifting between two mental tasks.

For younger students, have them sort a stack of word cards, first by meaning and then by sound. This is a well-researched method that has led to some impressive reading outcomes. One reason is because this activity mimics the constant shifting between language comprehension (meaning) and word recognition (sound) required for reading comprehension. (Remember our earlier discussion of the simple view of reading?)

For older students, switching between reading a text and annotating a text, or conducting online research and taking relevant notes, are ways to mimic the shift between basic comprehension of a text and deeper critical thinking about the text.

4. Support inhibitory control

Whether we know it or not, we use inhibitory control to manage many aspects of our lives. Every time we think before we act, we are using this skill. In reading, inhibitory control is what helps us suppress the common, everyday meanings of words in favor of their text-specific meanings. When we use context clues to determine that “duck” is a verb instead of a noun, for example, or that “canon” means a group of works in a specific discipline, not a weapon of war (spelled “cannon” by the way), we exert mental inhibition.

Tips for educators

Here are some ideas for addressing inhibitory control:

Show students how to approach multiple-meaning words in a text. Have them work with a partner or in small groups to create word maps that distinguish between the everyday meanings of words and the less common ones, including figurative and domain-specific meanings.

Show students how to resolve ambiguous meanings in texts. Use books of homonym riddles, idioms, or even dad jokes to turn this into a hilariously fun activity. Identify the misconception (ambiguous meaning) and then work together to resolve it. Embrace laughter and silliness along the way.

5. Support social understanding

Social understanding is what we use to make inferences in our daily interactions with other people. These inferences are based on our in-the-moment social, emotional, and cultural understanding of the world. In reading, we apply these skills to comprehend literary, historical, and social studies texts—all of which require social inference-making. We are flexing our social understanding every time we recognize humor (That’s so funny!) or irony (How ironic!) in a text, or when we grasp more sophisticated literary techniques, like foreshadowing or allegory (Oh, I see what the author is doing here. That’s a clever way of adding suspense).

Tips for educators

To help your class leverage social understanding when reading, try this:

Encourage students to “read the minds” of literary characters and authors. Try turning your classroom into a courtroom and putting a cast of characters on trial. Or mock interview an author in a class podcast: Why did you use this style? Why did you include certain facts and exclude others?

Encourage students to read widely and diversely. The more knowledge they have of the world—and the varied people, cultures, and ideas within it—the greater their potential for social understanding.

We can help set students on the path to becoming lifelong readers

Since I wasn’t a hyperactive kid, I wasn’t diagnosed with ADHD until I was an adult. Many girls and women aren’t. If I could teach that shy girl who was me all over again, I’d use the tips I’ve suggested here. While they’re good for all kids, they’re especially good for kids who have weak executive function skills. Kids like me.

I was lucky because I really wanted to be a reader, so I kept trying (and trying!) until I found my way. But perhaps I didn’t need to try so hard. I just needed to try something different.

Our challenge as educators is to find that “something different” for all our students—the thing that sets them on the path to becoming lifelong readers. They say it takes a village to raise a child. It takes a village to raise good readers and writers, too. We need to tap into that village if we want our students to become the flexible readers, writers, and thinkers we know they all can be—if given the right support!

Special thanks to Kelly B. Cartwright for her research on the five executive function skills most critical for literacy and many of the practical teaching tips recommended in this article.