When I taught science, I quickly learned that students were eager to think deeply when given the chance. If they could design their own experiments, use evidence and reasoning to support a claim, or develop models to explain real-world phenomena, motivation was never an issue.

When I taught science, I quickly learned that students were eager to think deeply when given the chance. If they could design their own experiments, use evidence and reasoning to support a claim, or develop models to explain real-world phenomena, motivation was never an issue.

In one unit on forces acting on a current-carrying wire in a magnetic field—the physics behind a simple electric motor—I showed my students a basic motor and challenged them to design an experiment. Their task was to test how changing one factor would affect the motor’s speed. Some experimented with wire gauge or the number of loops, others with magnet strength, magnet distance, or battery size. The result was unmistakable: every student was motivated. They would walk into class and dive straight into their investigations, often before the bell even rang.

This month’s release of the 2024 NAEP eighth-grade science report card made me think back to those experiences and wonder not only what today’s students are encountering in their science classrooms, but also how much they are actually learning. The national results offer a sobering answer.

Declines across the board

Achievement fell for students at every point on the scale, reaching lows not seen since NAEP changed its framework in 2009. Students at the top (90th percentile) dropped an average of two points, while those at the bottom (10th percentile) fell five points. In other words, everyone lost ground, but lower-performing students lost more, widening the gaps. For teachers, this means eighth-graders know less science than before, and the variation in knowledge across a classroom is greater—making effective instruction even harder than it was a few years ago. The modest progress made between 2009 and 2019 has now been erased, leaving students back where they were over a decade ago.

So what might explain this reversal? NAEP data point to two clear trends: fewer opportunities to engage in science practices and declining engagement. Building on these findings, a third factor may also play a role: reduced integration of literacy and science, something we infer from patterns such as English learners’ relative gains. Let’s consider each of these explanations in turn.

Explanation 1: Decline in science practices

One of the most striking findings from NAEP is the drop in opportunities for students to engage in authentic scientific practices. Students reported fewer chances to design investigations, use evidence to support claims, or construct explanations and arguments. These practices are at the heart of learning science, which is less about memorizing facts and more about learning to think and reason. NAEP results showed declines across a range of activities:

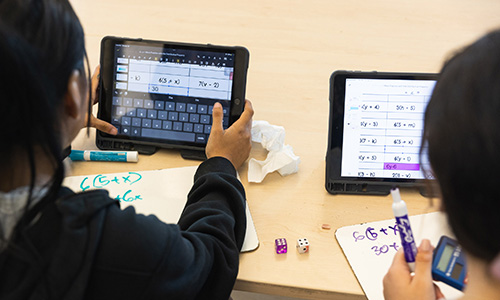

- Down two points for activities like coming up with research questions, using drawings to explain how something works, or designing experiments

- Down four to five points for using evidence from experiments to explain why something happens, using information to challenge an idea and improve an explanation, or applying math to support a scientific explanation or conclusion

What happens when we take away opportunities for students to engage in scientific practices? I think back to my unit on the simple electric motor. If, instead of letting students design and conduct their own experiments, I had only lectured, the experience would have been far narrower. Students might have read in a textbook about the force between a magnet and a current-carrying wire or solved a few problems estimating that force. But they would have missed the bigger picture.

My students would not have seen firsthand how adding a bigger battery increases current but also heats the wire, counteracting some of the benefit. Without testing different wire gauges, they would not have discovered that thicker wire reduces resistance and increases current, yet also adds mass to the loop, making it harder to spin. These are the kinds of tradeoffs that students uncover only when they are actively investigating—when they are doing science, not just hearing about it. And when practices decline, something else declines too: student interest.

Explanation #2: Cratering engagement

Student interest and enjoyment in science have cratered since 2019. NAEP shows that the proportion of students reporting interest and enjoyment dropped 9 to 10 percentage points, depending on the question. Engagement is closely tied to achievement: higher-performing students are much more likely to report enjoying and being interested in science than lower-performing students. For example, 65 percent of students at or above the 75th percentile agreed with the statement, “I think making an effort in science class is worthwhile,” compared to 38 percent of students below the 25th percentile. Declines in engagement are both a consequence of fewer opportunities to engage in science practices—students aren’t experiencing the thrill of inquiry—and a contributing factor to lower achievement, since motivation drives effort and learning. With students losing both knowledge and enthusiasm, helping them recover from pandemic-era setbacks will be an even greater challenge.

Providing opportunities for students to engage in the practices of science is essential to motivation, and it is also a primary way for students to build literacy skills. This makes reduced opportunities to connect reading and writing with science a possible contributor to the decline in scores.

Explanation #3: Missed opportunities for science–literacy integration

As noted earlier, when students have fewer opportunities to engage in the practices of science, they also lose chances to explain and argue their ideas. Explanation and argumentation are literacy-intensive practices, central both to learning science and to developing reading and writing skills. Without regular opportunities to discuss, write about, and use language to make sense of what they observe, students miss a critical pathway for deepening understanding.

One NAEP finding makes this especially intriguing: English learners bucked the national trend, with their average science score rising six points since 2019, while scores for non-English learners fell by three points, returning to around 2009 levels. NAEP does not report how instruction differs for these groups, but it is reasonable to think that emergent multilingual students may receive more consistent opportunities to read, write, and talk about science as part of their language development. If so, their steady upward trajectory since 2009 suggests that maintaining literacy-rich science instruction can pay dividends for both engagement and achievement.

While NAEP does not directly measure integration, the contrast between English learners and their peers hints at the instructional leverage that science–literacy integration might offer, especially in classrooms working to recover from pandemic-era disruptions.

Weaving the explanations

Taken together, these findings suggest that the challenges to improving science instruction are not isolated. Fewer opportunities to engage in the practices of science mean students are less likely to experience the curiosity and excitement that drive motivation. Lower motivation, in turn, makes it harder for students to persist when concepts are difficult, further dampening achievement. At the same time, when students are not regularly explaining, arguing, and writing about their ideas, they miss a critical bridge between science and literacy—one that may have supported English learners even as their peers lost ground. In short, declines in practice, engagement, and integration are deeply interconnected, creating a cycle that makes recovery more difficult if any one strand is ignored.

Back to the classroom

When I think back to my own teaching, the lessons that most energized my students were those where they were doing science rather than just hearing about it. The electric motor unit was one example, but the same dynamic played out across topics. When students had a problem to solve, materials in their hands, and space to explain and argue their findings, their motivation soared. They weren’t just learning about science; they were becoming scientists in the classroom.

The NAEP results remind us that if we want students to recover from recent declines, we can’t focus only on content coverage. We need to design classrooms where investigation, engagement, and language are woven together. That means protecting time for inquiry, making space for talk and writing, and nurturing curiosity. These are not extras—they are the very conditions that make science learning meaningful and lasting.

As educators, leaders, and policymakers look for next steps, I hope they see that the path forward is not just about more science, but about richer science. The kind where every student, regardless of background or language, has the chance to ask questions, test ideas, and explain their thinking. That’s how we rebuild not just scores, but the joy of science itself.