Early in my career, I taught kindergarten, and mornings often started on the carpet. Not long into each school year, we clapped syllables in our names—An-drew, Ma-ri-a—and the room buzzed with confidence. Students laughed as they discovered who had the longest name and, when prompted, proudly volunteered words that rhymed with cat. Everyone wanted a turn. It felt like a win.

Early in my career, I taught kindergarten, and mornings often started on the carpet. Not long into each school year, we clapped syllables in our names—An-drew, Ma-ri-a—and the room buzzed with confidence. Students laughed as they discovered who had the longest name and, when prompted, proudly volunteered words that rhymed with cat. Everyone wanted a turn. It felt like a win.

The first year I tried that lesson, I transitioned to some small group work and asked a seemingly simple question: “What’s the first sound in cat?” The energy shifted. Hands stayed down. A few students looked at the floor. Others quietly repeated the word cat to themselves, unsure how to pull it apart. These were the same students who had just been successful with rhyming and syllables, but this task felt different.

That moment stayed with me. It was not that the students did not know language or sounds, I soon realized. It was that I was asking them to work at a deeper level of sound awareness. What I was seeing, in real time, was the difference between phonological awareness vs. phonemic awareness. My students were confident with larger sound units, but isolating individual sounds was a new and more complex step.

Understanding that distinction and teaching it intentionally makes a powerful difference in how students learn to read. And it is a distinction worth exploring carefully.

What are phonological awareness and phonemic awareness?

Learning to read begins long before students encounter print. At its core, reading requires students to understand that spoken language is made up of sounds—and that those sounds can be analyzed and manipulated.

Phonological awareness refers to a broad set of skills related to recognizing and working with sounds in spoken language. This includes noticing words in sentences, clapping syllables, identifying rhymes, and recognizing onsets and rimes. These skills focus on sound structures in spoken language and may be taught with or without the support of letters or written text, depending on instructional purpose and student need.

Phonemic awareness is a more refined skill within this broader category. It refers specifically to the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate individual sounds—phonemes—in words. For example, recognizing that the word cat is made up of the sounds /c/, /a/, and /t/ requires phonemic awareness.

Both skills are emphasized in the science of reading, which highlights the importance of explicit, systematic instruction in the foundational components that support decoding and spelling.

Is phonological awareness the same as phonemic awareness?

No. Phonological and phonemic awareness are related, but they are not the same.

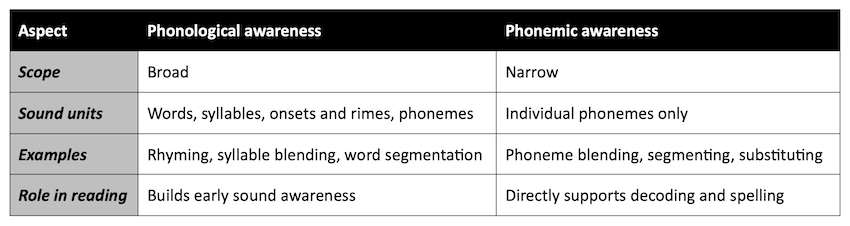

These two terms often get used interchangeably, which is completely understandable. Both deal with listening to and working with sounds in spoken language. The key difference is the size of the sounds students are working with. Phonological awareness covers a broad range of sound skills, like rhyming, clapping syllables, and breaking words into parts. Phonemic awareness zooms in on just one thing: individual sounds, or phonemes, in words.

Is phonemic awareness part of phonological awareness?

Yes, it is. Think of phonological awareness as the big umbrella, with phonemic awareness underneath it. As students become comfortable noticing and working with larger sound units, they are better prepared to move into the more advanced work of hearing, separating, and changing individual sounds in words. This progression helps students build the sound foundation they need for reading and spelling.

What is the difference between phonological awareness and phonemic awareness?

The primary difference between the two lies in the size of the sound units students are working with.

Understanding this distinction helps educators match instruction to students’ developmental needs.

Understanding this distinction helps educators match instruction to students’ developmental needs.

What comes first, phonological awareness or phonemic awareness?

Phonological awareness comes first.

Students typically develop awareness of larger sound units, such as words, syllables, and rhymes, before they are able to isolate and manipulate individual phonemes. These early phonological skills provide the foundation upon which phonemic awareness is built.

What is the importance of phonological and phonemic awareness?

Phonological and phonemic awareness are some of the strongest early predictors of reading and spelling success. When students can hear and work with the sounds in spoken words, they are better prepared to connect those sounds to letters when they begin decoding and spelling.

I saw this clearly one year in my classroom when two students knew all their letter names and sounds, but only one could break words apart by sound. When we started spelling simple words like sun and map, one student could slowly stretch the sounds and write each letter. The other guessed, even though they “knew” the letters. The difference was not phonics; it was phonemic awareness.

Phonological awareness helps students notice patterns in language, such as rhymes and syllables, which supports word recognition and fluency. Phonemic awareness takes it a step further by allowing students to isolate, blend, and change individual sounds. These skills are essential for sounding out new words and for spelling them accurately. When these skills are taught early and explicitly, they give students the sound foundation they need to become confident, capable readers.

Levels and progression of phonological and phonemic awareness skills

Sound-awareness skills generally develop along a continuum, moving from larger to smaller units of sound:

- Awareness of words in sentences

- Awareness of syllables

- Awareness of onsets and rimes

- Awareness of individual phonemes

As students reach the phonemic level, they learn to:

- Isolate sounds

- Blend sounds

- Segment sounds

- Add, delete, or substitute sounds

This progression highlights why instruction should be intentional and developmentally sequenced.

Is rhyming phonological awareness, or is it phonemic awareness?

Rhyming is a phonological awareness skill.

Because rhyming involves larger sound units, rather than individual phonemes, it falls within phonological awareness, not phonemic awareness.

Phonological awareness vs. phonemic awareness examples

Here are two sample tasks, alongside sample student responses, that can help you get a better sense for the difference between broader phonological skills and phoneme-specific skills.

- Phonological awareness task. Teacher: “Which words rhyme with log?” Student: “Dog. Frog. Hog.”

- Phonemic awareness task. Teacher: “What happens if we change the /l/ in log to /f/?” Student: “Fog.”

Phonological and phonemic awareness activities and lesson plans

Strong instruction in phonological and phonemic awareness is explicit, systematic, and engaging. Students benefit most when these skills are taught intentionally, practiced frequently, and revisited across the day in short, meaningful routines. Instruction should move from larger sound units to individual sounds and be responsive to student need.

Effective classroom activities include:

- Clapping and counting syllables. You can model how to clap or tap syllables in students’ names, classroom objects, or vocabulary from read alouds and content areas. This helps students hear how words break apart into meaningful sound chunks and supports early phonological awareness.

- Rhyming routines. Using songs, poems, and picture cards, students can generate, identify, and sort rhyming words. You might ask, “Which words sound the same at the end?” to build attention to sound patterns without requiring print.

- Picture sorting by sound features. Students sort pictures by rhyme, syllable count, or beginning sounds. These activities provide visual support while keeping the focus on listening and speaking. Picture sorts are especially effective for small group instruction and intervention.

- Oral blending routines. You say sounds slowly, such as /m/ /a/ /p/, and students blend the sounds to say the word. This routine directly supports phonemic awareness and prepares students for decoding once letters are introduced.

- Oral segmenting routines. Students practice breaking words into parts by tapping, moving counters, or using their fingers to represent each sound. For example, students might tap three times to represent the sounds in sun.

- Sound manipulation activities. You guide students in adding, deleting, or changing sounds in words, such as, “Say map. Now change the first sound to /t/. What word do you have?” These tasks represent advanced phonemic awareness and should be introduced after students demonstrate readiness.

- Brief, daily practice. Research shows that short, frequent practice is more effective than longer, less frequent lessons. Embedding sound awareness routines into morning meetings, transitions, or literacy blocks helps students build and maintain these skills over time.

When phonological and phonemic awareness instruction is intentional and aligned to student development, it builds a strong foundation for decoding, spelling, and fluent reading.

Phonological and phonemic awareness assessment

Assessment of sound awareness skills should be oral, efficient, and directly connected to instruction. You can use informal observation, quick checks, and screening tools to determine where students are along the phonological and phonemic awareness continuum. Listening closely as students blend, segment, or manipulate sounds provides valuable insight into what they can do independently and where they may need additional support.

Interim assessment tools, such as MAP® Reading Fluency™, also play an important role in this process. MAP Reading Fluency helps educators understand how foundational skills like phonological and phonemic awareness are contributing to students’ overall reading development. By examining student performance data alongside classroom observations, you can identify patterns, monitor progress over time, and make informed decisions about targeted instruction, small group support, or intervention. When assessment is used intentionally, it ensures students receive the right instruction at the right time to continue building strong early literacy skills.

In closing

Understanding phonological awareness vs. phonemic awareness gives educators clarity about how early reading skills develop and how to teach them effectively. When instruction intentionally moves from broad sound awareness to precise phonemic manipulation, students are better prepared to decode, spell, and ultimately comprehend text. Strong foundations in sound awareness open the door to confident, capable reading.