Not all disciplines are created equal. A hierarchy has been created within our education system based on our attention, funding, and graduation requirements in selective school subjects. While the arts and humanities have long struggled for a place at the table with any of the core classes, social studies and science have also fallen short of the spotlight that rests on English language arts and mathematics. But I’d argue one more tier exists that segregates mathematics from ELA, and we should be talking about it. Doing so can help more students develop a growth mindset in math class.

Not all disciplines are created equal. A hierarchy has been created within our education system based on our attention, funding, and graduation requirements in selective school subjects. While the arts and humanities have long struggled for a place at the table with any of the core classes, social studies and science have also fallen short of the spotlight that rests on English language arts and mathematics. But I’d argue one more tier exists that segregates mathematics from ELA, and we should be talking about it. Doing so can help more students develop a growth mindset in math class.

A Cinderella story

Among the disciplines, math continues to be seen as the estranged sibling, forced to do the boring chores and not allowed to attend the grand ball. The years of math anxiety, standardized testing, hyperfocus on rote memorization, discrimination, and a singular fixed track of high school math courses have turned math from a thinking discipline that opens up a world of possibilities into a feared progression of topics that many students struggle to grasp, which leads to many of them checking out, burning out, and sometimes dropping out.

The way people feel about mathematics as they enter their adult lives is highly indicative of the way the discipline was treated while they were in school. Now, perhaps more than ever, our youngest generations are interested in understanding how what they are learning connects with the big picture. Mathematics continues to be defined by a lack of unification about its instruction and how it should be assessed, however, and this has resulted in not only a lack of connection but also double standards, when we consider how ELA is taught. Acknowledging—and addressing—these double standards can help math educators improve their students’ relationship to math, which can lead to higher engagement and academic achievement.

Double standard #1: The “one right answer” fallacy

The structure of math class has long been obsessed with finding the single right answer. Our summative tests usually support this point of view and even measure proficiency by it. Beyond that, even the process by which we expect students to obtain the correct answer has become standardized into “one ideal way to solve”: the standard algorithm.

In an ELA class, on the other hand, students learn to write through consistent trial and error. Iteration, creativity, rewriting, and editing are expected and considered crucial components of the writing process, in many ways more important than the final draft.

Double standard #2: The “math person” cop out

For one reason or another, many students enter adulthood disliking or even hating math. Either they didn’t find the way mathematics was taught appealing, didn’t find success in standard algorithms, or didn’t have a teacher who illuminated the true value mathematics brings. Then something rather strange happens. These adults begin to use the blanket excuse “I’m not a math person” for every subsequent case where math creeps into their reality. As if a “math gene” is something we are either born with or not. The worst part is not necessarily that people use this excuse, but that it is generally accepted by society when they do; a person is allowed to continually adhere to this fixed mindset, instead of encouraged to develop a growth mindset in math class.

And is there an ELA equivalent of such an excuse? Not to the same degree. Imagine a person having gone through traditional schooling who simply checks out of all situations where reading is involved, claiming they “aren’t a reading person.” Selective illiteracy is not welcomed with the same open arms as math aversion. In many cases, choosing not to read would be met with far more judgment than math avoidance and seen as unacceptable in today’s world.

Double standard #3: The “real world” restriction

Another odd requirement for math class that has developed over time is the prerequisite that every bit of content students are expected to learn should apply to “real life.” The age-old question “When am I ever going to use this?” is asked aloud often and is used almost as a free pass for students to lose interest if their teacher can’t come up with a convincing answer. And even if a teacher can give a solid answer, students aren’t usually convinced.

Now imagine a language arts class where students are reading a long informational text about the life and adaptations of penguins. Do these same students stop mid-passage to ask the same “When will I ever use this” question? Not as much. ELA teachers often use a variety of topics to provide their students numerous unique opportunities to become better readers, thinkers, and writers. The topic of a passage isn’t the point of the lesson; the skills being developed through the passage are.

Challenging the double standards

Instead of focusing so heavily on the outcome of mathematical work, we should reorient our instruction to primarily value the thinking involved, both in our words and our actions. Instead of allowing statements like “I’m not a math person” to float into conversation unchallenged, we should facilitate conversations about the many skills mathematics courses teach us and how we continue to practice those in our lives each day. Instead of allowing students to ask when they are ever going to need the Pythagorean theorem, for example, we need to reframe the purpose of all mathematics topics. We must make it clear how these topics are entry points by which we can all practice the skills we will need in “real life,” things like pattern recognition, logic, reasoning, estimation, problem solving, and decision making.

In many ways, teachers have their work cut out for them in helping students develop a growth mindset in math class, but ownership of how we talk about the discipline belongs to all of us. With concerted efforts in a few key practices, we can all help students see math as the strong princess she is, one fully worthy of attending the grand ball.

Practice #1: Reframe math as a journey, not a destination

No matter how many times kids may ask us if we’re there yet, focusing on the journey, rather than the destination, can be a valuable way to support them in making a shift.

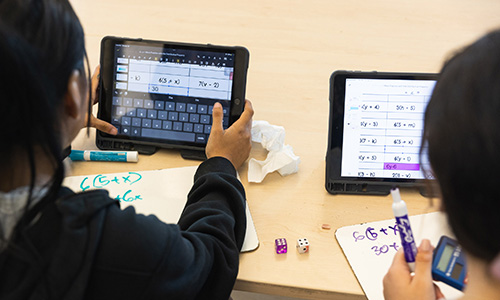

Teach students to realize what’s important in math class. Show the value of all the thinking that comes prior to finding an answer. By asking great questions, seeking out multiple perspectives, trying various strategies and comparing them, encouraging discourse, and finding alternate solutions, you can shift the focus from finding the right answer to doing the right kind of thinking.

Practice #2: Develop growth and opportunity mindsets

It can be challenging to prove that everyone is a math person. But with specific, consistent effort and a belief that everyone can improve, you can show all your students that they, too, can strengthen their skills and gain confidence.

The shift to a growth mindset in math class depends on building a pro-math culture, and beginning this work can be as simple as considering the language we use. How we talk about mathematics and how we talk about ourselves as mathematicians say a lot about the beliefs we hold, and these attitudes can shape our learning approaches and performance in the discipline.

Acknowledge that upholding a fixed mindset about math achievement has been shown to affect how a teacher sees students, often stunting their growth and limiting their potential. Embrace an opportunity mindset, an intentional attitude about being proactive and seeking out opportunities to learn. Be willing to share your own journey with math and how it has changed you over time, too. Even as a teacher, you have chances to discover new things, and taking that journey alongside your students can help foster their relationship with the discipline.

Practice #3: Study math yourself

Has it been ages since you wrestled with a math problem? Take one on and discover the interconnectedness of the discipline on your own to bring concepts to life for students.

Research suggests that content-focused professional development is one of the greatest factors contributing to the kind of instruction that increases student achievement. It also shows that teachers with more opportunities for professional development in mathematics feel more comfortable teaching advanced topics, which brings about quicker student growth than basic, repetitive skill instruction.

Practice #4: See math as its own context

Math doesn’t need “real world” context to be relevant; the concepts through which students practice valuable reasoning and problem-solving skills are valuable on their own. And while “real world” application can bring about stronger engagement in mathematical inquiry, it is certainly not a precursor.

The next time a student asks, “When am I ever going to use this?”, redirect them to think more critically about the transferable skills being developed by the explorations in the topic. Perhaps the buy-in students need lies within their own understanding of the bigger picture—the “why”—not a one-off explanation about where we use parabolas in our daily adult lives.

Practice #5: Embrace individuality in math class

While it’s true that everyone is a math person, it’s also important to allow students to find themselves within the discipline. More than ever, the youngest generations are looking for identity and belonging in the things they are learning; in fact, some research has connected this need to belong with predictions for achievement in algebra, especially among underrepresented groups.

Build up a classroom community of students who embrace challenge and learning by modeling how positive self-talk can facilitate tackling an especially thorny problem. Create a group of learners who see a variety of topics in math less as not applicable or perhaps detached from the “real world” and more as new, unique avenues for applying their foundational skills that carry through to adulthood.

Uphold creative strategies and embrace the power in “finding your own way” and deriving meaning. Assist students in finding their unique strengths within the discipline. A strong math culture embraces a variety of perspectives and skills. With math as more than a discipline focused on finding the answer, creativity and reasoning can flourish. And so long as we are moving away from a “single correct answer” mindset, let’s redefine proficiency in mathematics while we are at it.

Taking back the power of mathematics

Some of our traditional and common approaches to mathematics instruction keep the beauty of the discipline from shining through. Using these outdated mindsets and practices, we inadvertently create more generations of humans who can’t see the math person inside. But by taking a stand and reclaiming the discipline with a few of the strategies I mentioned above, you can bring about very powerful and life-changing experiences for your students who have every ability to see themselves as math people. We simply need to reawaken or just welcome to the forefront the curious and creative being within each of them.