My daughter, who is in middle school, has dreams of being a veterinarian. One night, while looking for a program to watch, she found Dr. Oakley, Yukon Vet on Disney+. It’s a series about a veterinarian who helps all kinds of animals—from pets to farm animals to rescued wildlife—in the Yukon and Alaska. In each episode, viewers follow the vet as she treats different animals, describing procedures using both simple language and medical terms.

After a few episodes, my daughter began to pick out some of the medical terms and ask me what they meant. “What is a hematoma, Mom?” I know about many things, but medicine is not one of them. “Let’s look that one up!” I suggested, and we did a quick search online. (A hematoma is a collection of clotted blood in the body, for those who are wondering.) Then, the other day, she told me her class was reading The Red Pony by John Steinbeck. She and her peers were asked to debate whether the pony had been well taken care of, and my daughter used some of what she learned from Dr. Oakley to win her arguments.

My daughter’s experience is an example of how the vocabulary children learn helps them interact with and understand text. In this article, I’ll explain what it means to “know” vocabulary, how it helps us read and understand what we are reading, and how families can help their children build their vocabulary.

What is vocabulary and why is it important for reading?

If you ask someone if they know a particular word, they might respond by telling you what it means. But most people don’t realize that to “know” a word means so much more than just knowing its definition.

Vocabulary is all the knowledge a person has about a word, which includes knowing what it means, when it is used, how to say it, and how to use it in a sentence. This knowledge also includes all the other ideas and terms connected with the word. For example, if you know the word “dog,” you probably also know that dogs can have a variety of relationships with people, such as being family pets, guiding the visually impaired, and working for the police and military. You might be able to picture different breeds of dogs, and you probably understand that certain words, such as “collar,” “leash,” and “fetch,” are associated with dogs. All that information helps you understand the word “dog” and know how to use and interpret the meaning of the word in text.

Having a large bank of vocabulary knowledge is one of the most important elements that can help a child make sense of text. The more vocabulary a child knows about what they are reading, the more they are able to comprehend, or make sense of, the text.

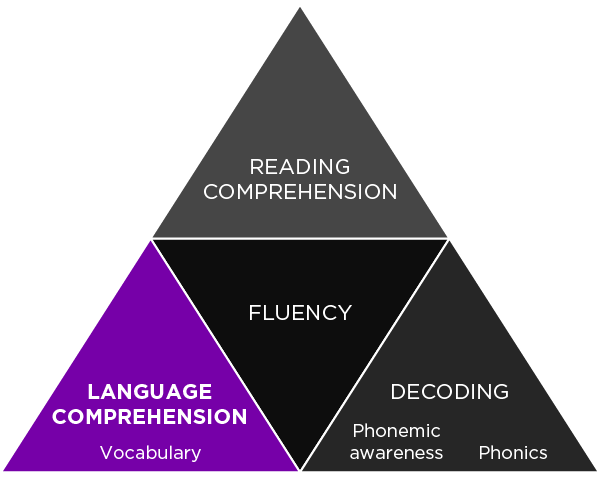

Here’s a graphic that shows how vocabulary helps support reading comprehension. The top piece of the triangle is reading comprehension, or how we make sense of what we read. This is the key goal of reading. The two skills needed to reach this goal make up the bottom two pieces of the triangle: language comprehension and decoding, which includes phonemic awareness and phonics.

The Simple View of Reading

Vocabulary knowledge is part of language comprehension, but it also contributes directly to word recognition, which helps with fluency, shown in the center of the pyramid. Fluency, or the ability to read with an appropriate rate, accuracy, and expression, affects how well a person reads and understands what they read.

Vocabulary knowledge is part of language comprehension, but it also contributes directly to word recognition, which helps with fluency, shown in the center of the pyramid. Fluency, or the ability to read with an appropriate rate, accuracy, and expression, affects how well a person reads and understands what they read.

The power of knowing many words

Let me give you an example of how a rich, deep knowledge of vocabulary helps reading comprehension. Let’s take the word “close.”

Depending on what the sentence is about (the context) and where “close” is positioned in the sentence (what part of speech it is), “close” could be an adjective and mean “nearby” (“The store is close to my house”) or it could be a verb and mean “to shut” (“Please close the door”).

Because you know that word, you understand that even though the spelling is the same, the meanings are different, the role it plays in the sentence is different (one is an adjective and the other a verb), and the way you say it is also different. There are so many examples in English of words like this, but your vocabulary knowledge helped you sort it all out.

How kids learn vocabulary

Once kids start school, they will learn vocabulary in the classroom, but that is only one way to build vocabulary. Research by the National Institute for Literacy has found that children learn most of their vocabulary outside the classroom by reading on their own, listening to books read to them, having conversations with others, or watching something, as my daughter did. New information, experiences, and thinking all combine to build knowledge about words, and this happens throughout a person’s life.

The more children learn about the world, in the classroom or out, the more prepared they will be to understand what they are reading because of the knowledge they have. Research out of Harvard has also shown that the vocabulary development of young children impacts their ability to read and do well in school in later years.

5 tips for home

Families can provide a lot of information to their children, such as word meanings or other details about a word, that can help them build their vocabulary. Here’s how.

1. Read to and with your children, as often as you can

Simply reading to children, taking turns reading with them, and having them read to you will help build vocabulary. You can do this with children of any age.

The more variety in what you and your child read, the better. Read about different topics, read fiction and nonfiction, read magazines, chapter books, or graphic novels. Each offers different vocabulary, language usage, and information that can help provide meaning later on.

Read a book from the Llama Llama series by Anna Dewdney to your kindergartener or Because of Winn-Dixie by Kate DiCamillo to your third-grader, for example. Is your middle-schooler reading a Steinbeck novel? Take turns reading parts! Even 15 minutes of reading together is 15 minutes more than they would have gotten without your support.

2. Get curious about language

Turn your reading time into a word party! Talk to your child about interesting or unknown words you stumble across during your reading. Are there words that sound interesting, funny, or particularly beautiful? Are there words they struggled with or couldn’t define? This will give them the opportunity to ask questions and understand how each word fits into the story.

Don’t be afraid if you don’t know every word you read together. You are setting a great example if your child sees that you are also learning new words.

3. Look for clues to define new words

When your child doesn’t know a word, try different strategies to encourage them to determine its meaning:

- Ask them to read the sentences before and after the word to look for clues about the meaning of the unknown word. Can they guess what the meaning might be?

- Talk about the parts of the word, also referred to as morphology. What part of speech is the new word? Are there prefixes, such as “pre-” or “un-,” or suffixes, such as “-ous” or “-able”? How do they affect the meaning? Is the main part of the word (the root) Greek or Latin? Reading Rockets’ “Root words, roots and affixes” can help.

- Try to categorize the new word. Does it seem like it might be an action? A feeling?

Once you’re done tackling the word mystery together, see if you were right. Show your child how to look up the meaning of words in a dictionary, and explain how most will include information on the part of speech.

4. Play with synonyms and antonyms

Spend some time talking about synonyms, words with the same meaning, and antonyms, words that are opposites. Do this with both the words you got curious about together and the ones you had to investigate.

Connecting new vocabulary to known words can help make it easier to remember. Are there experiences your child has had that can help them connect to the new vocabulary? If you’re working with the word “arduous,” for example, remind them how “hard” or “difficult” it was to build that LEGO set last weekend. With any luck, they’ll reply, “Yeah, that was arduous!”

5. Practice

Just defining a new word isn’t usually enough to really learn and remember it. The more your child uses new vocabulary, the more they will remember it. Here are some ways to encourage practice and repeated exposure to new words:

- Have your child say or write a sentence with the word, or even act it out. Playing around with putting a word to use can help its meaning stick.

- Encourage your child to read more than one text about a topic. This will give them more opportunities to have contact with new vocabulary.

- Use new words. A lot. Set a fun goal for yourself to use only a new word, instead of its more familiar synonyms, for a day or even a week. This weekend’s family hike won’t be hard. It will be arduous!

There’s no time like the present

Reading changes lives, and a strong vocabulary makes all of us stronger, more confident readers. To learn about other ways to support your child, see the Teach. Learn. Grow. archive of articles on supporting families.